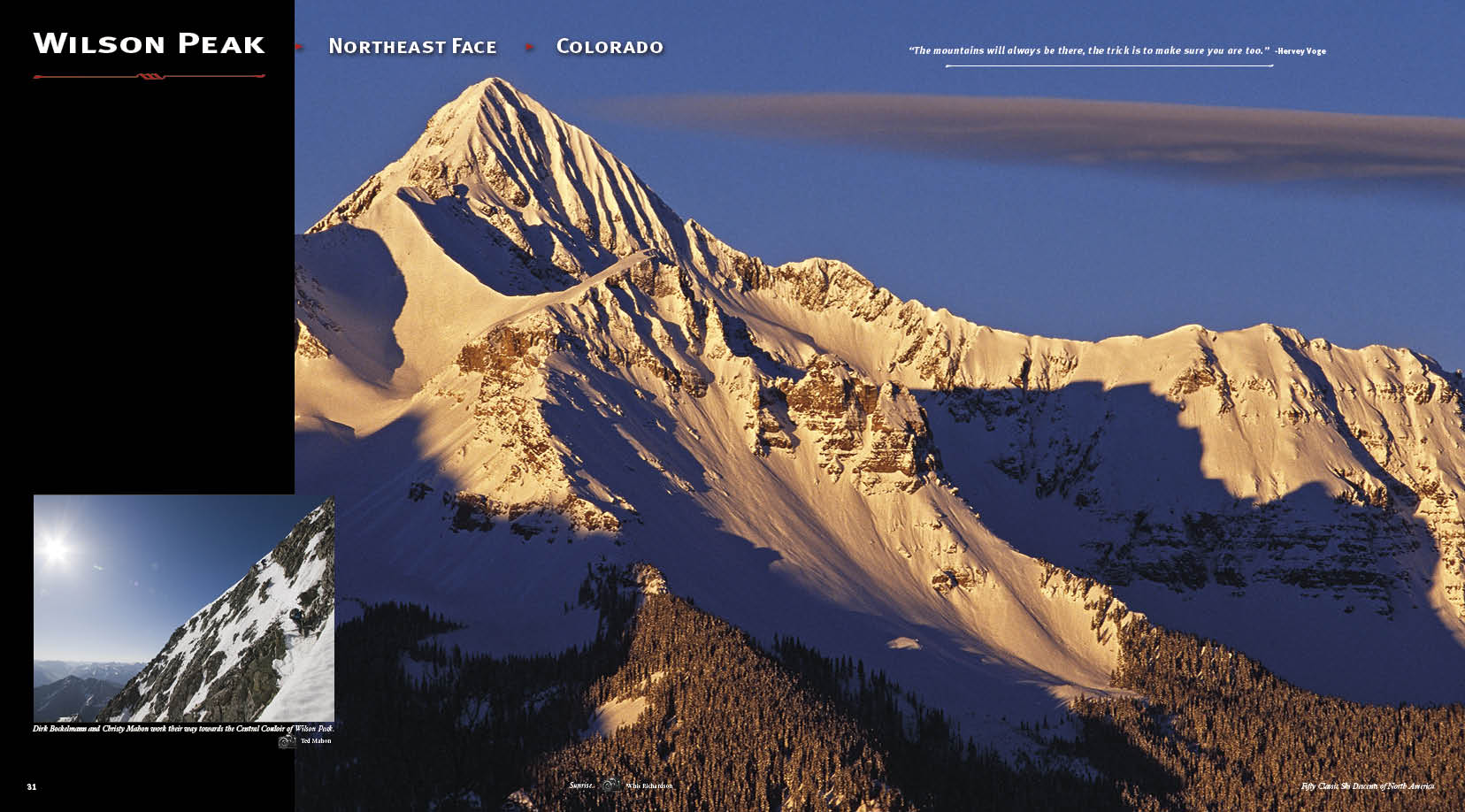

Colorado ski alpinism is characterized by many high altitude ski options. With fifty-four peaks over 14,000 feet and over 600 summits over 13,000 feet the list of potential classics is big. Narrow chutes, vast open faces and thousands of well-defined avalanche paths on every aspect await skiers willing and knowledgeable enough to explore the six major ranges in the state. • The Elk Range gets abundant snow, has many of the more dramatic descents and is blessed with less wind than the mountains near the continental divide. • In contrast, the Front Range collects snow via aggressive wind transport into a myriad of steep sustained couloirs that provide great descents into June during most years. • The San Juans have a special quality to them on a good snow year. Deep accumulations of higher water content storms fill huge paths, offering amazing vertical and superb snow conditions when the powder harvests are primed. • The Gore is a seldom traversed and explored range of compact and dramatic geography. Surrounded by populated areas on several sides, it is ripe for more winter exploration by modern, lightweight cold smoke seekers. • The Sawatch and Sangre de Cristo ranges have huge, rarely skied routes due to lean mid-winter snows and bigger wind events. However they can be spectacular for ski alpinists paying attention to the monstrous, moisture laden lows that spin out of the southwest in late winter and spring. • Spectacular geography, good weather, snow, minimal wind and especially the companions you ski with make a descent truly classic or just another challenging foray above 12,000 feet. • We selected five for the Colorado section, but many options and variations await skiers with the tenacity to learn, ascend and perch themselves high on the lofty summits of Colorado at just the right moment. Timing is everything in life and successful big ski descents are no different.

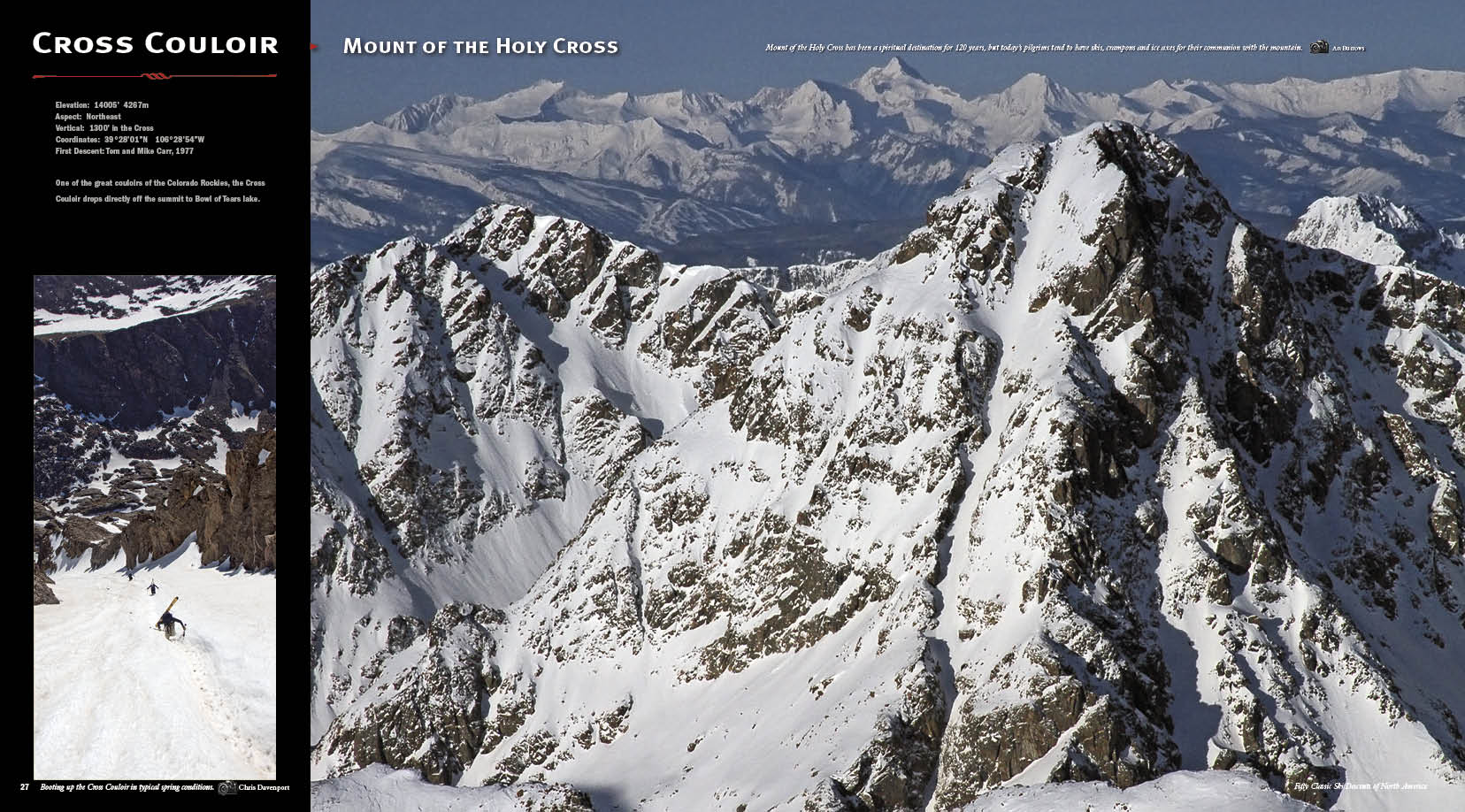

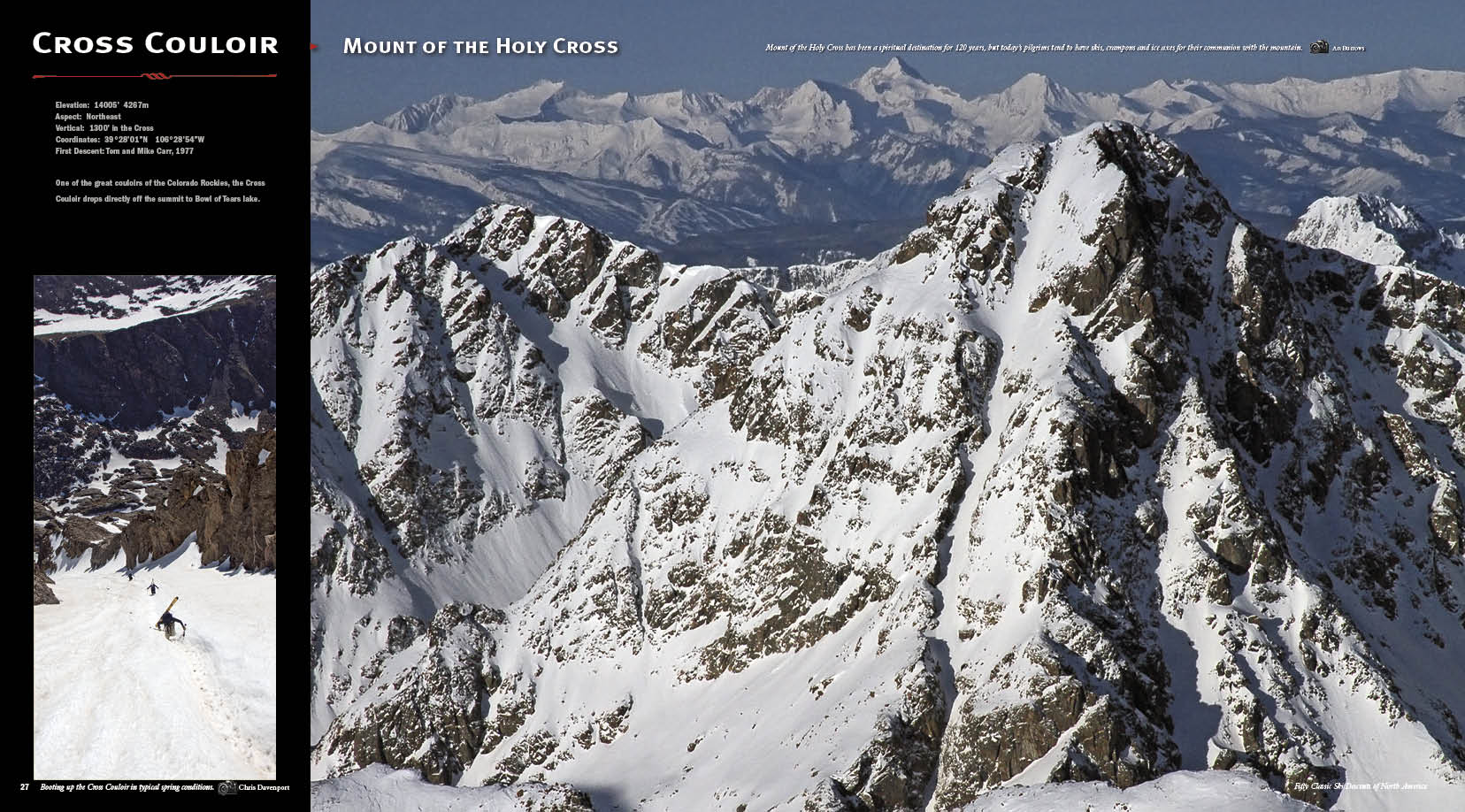

Elevation: 14005’ 4267m

Aspect: Northeast

Vertical: 1300’ in the Cross

Coordinates: 39°28’01”N 106°28’54”W

First Descent: Tom and Mike Carr, 1977

One of the great couloirs of the Colorado Rockies, the Cross Couloir drops directly off the summit to Bowl of Tears lake.

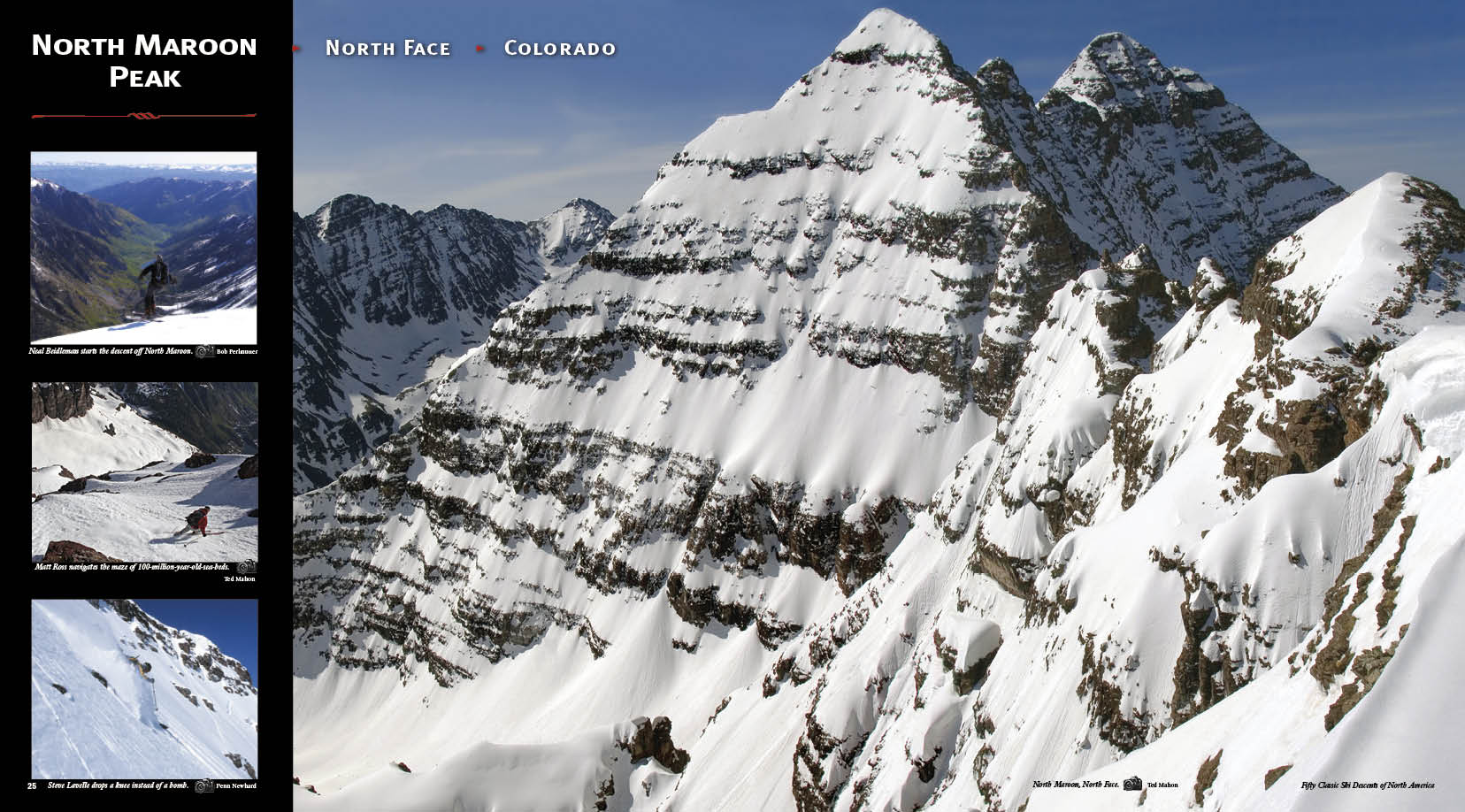

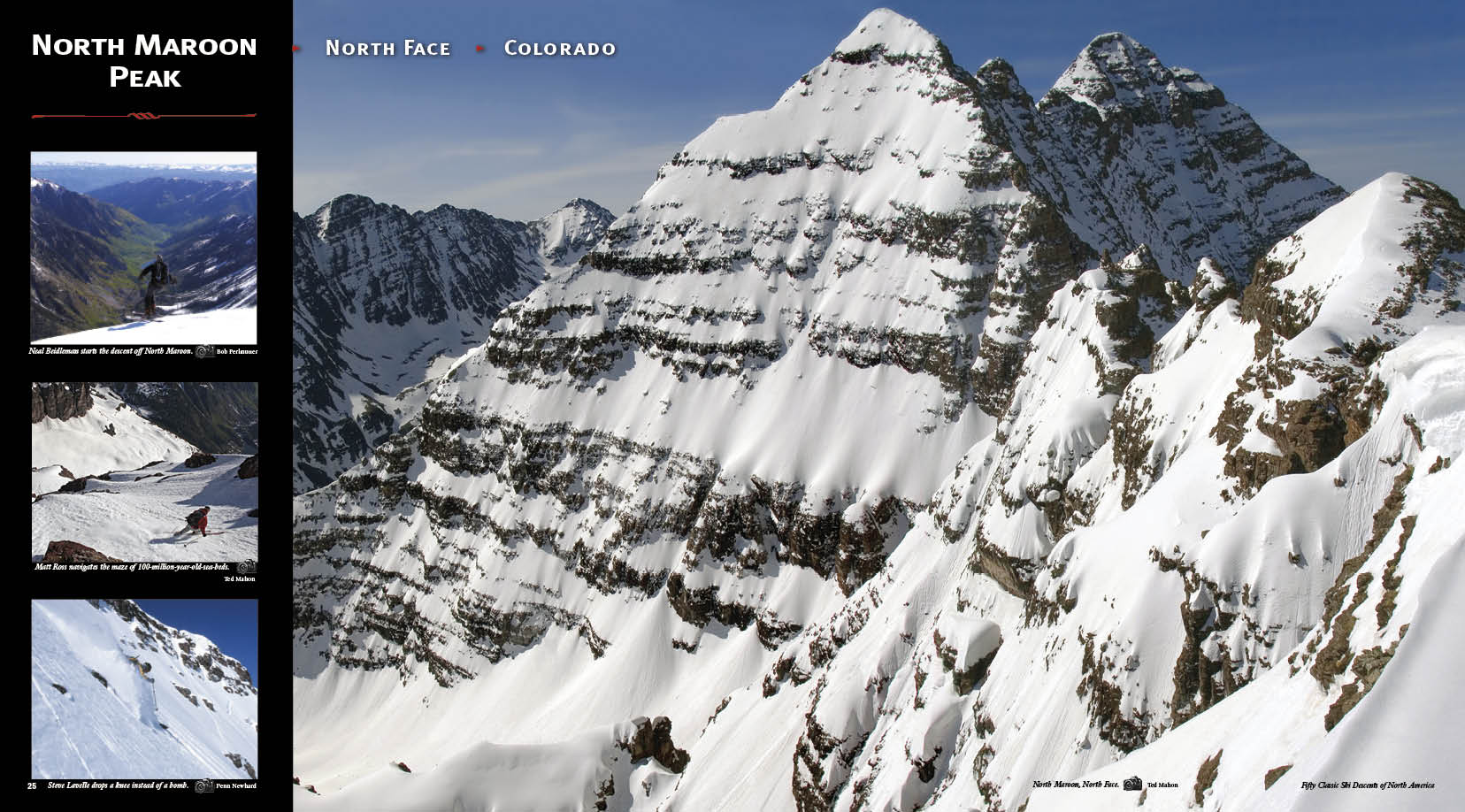

Elevation: 14014’ 4271m

Aspect: North Face

Vertical: 4000’

Coordinates: 39º 04’ 34” N 106º 59’ 14” W

First Descent: Stammberger, 1971

A visual icon with a complex line. Also mutiple options between the two peaks and aspects.

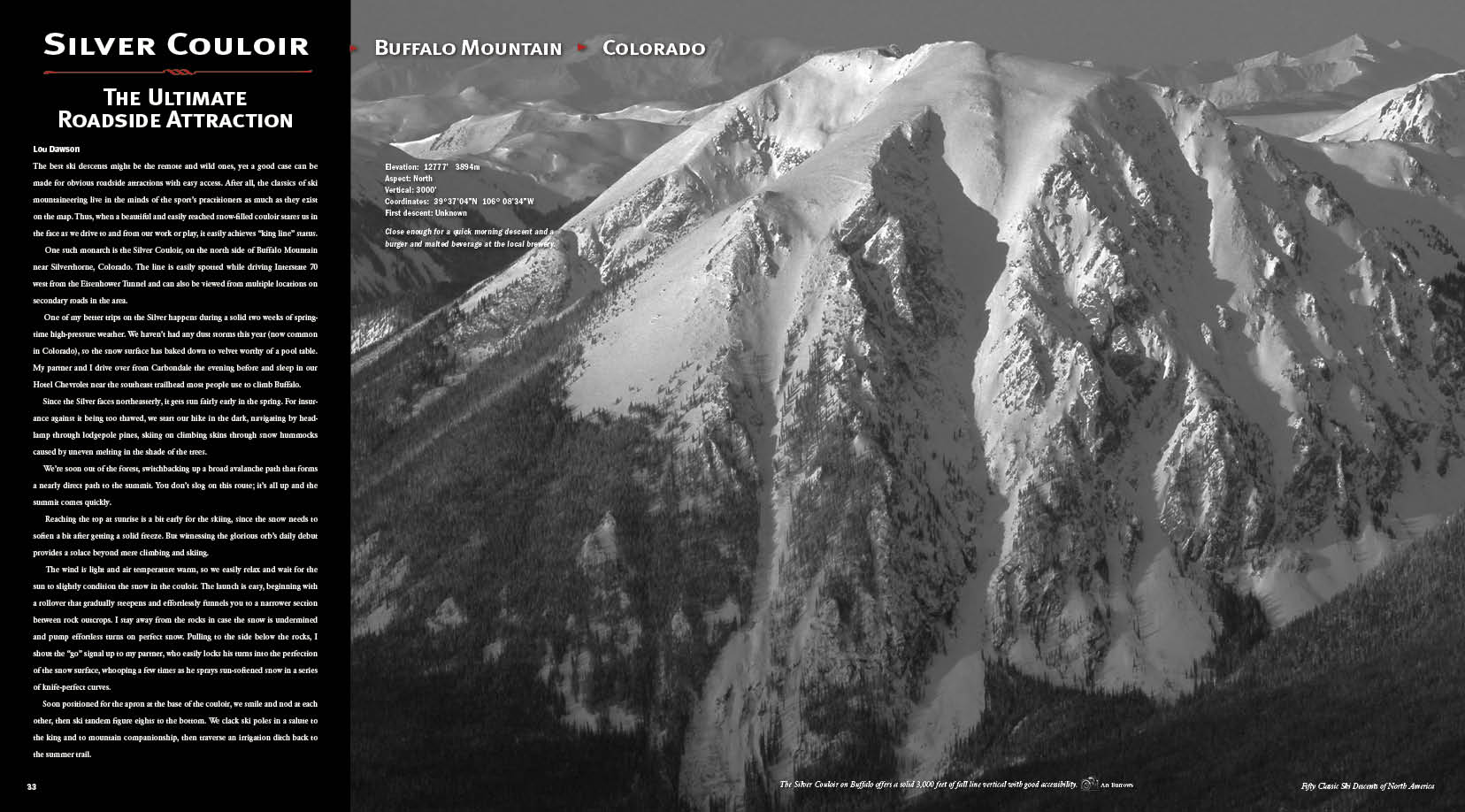

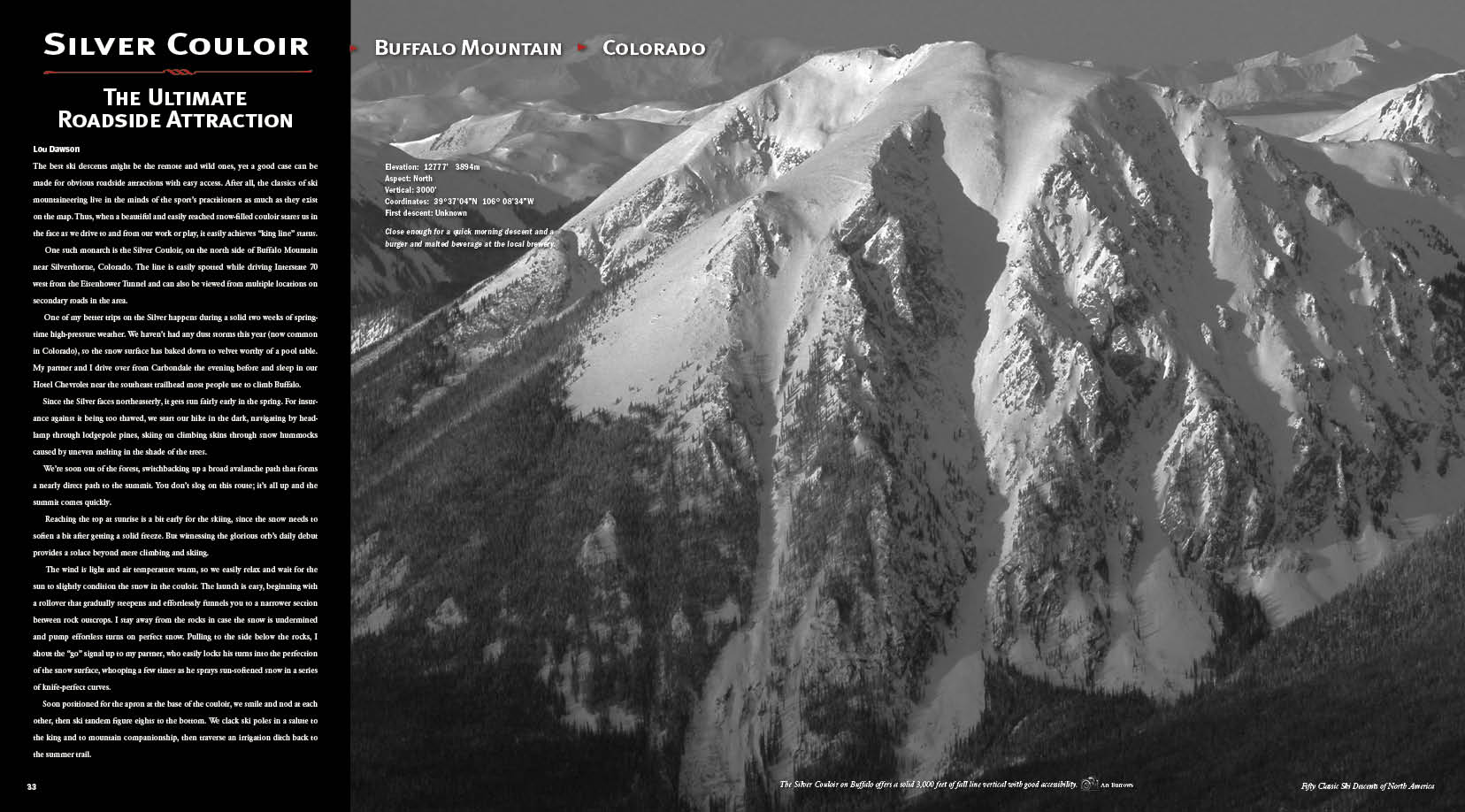

The Ultimate Roadside Attraction

Lou Dawson - The best ski descents might be the remote and wild ones, yet a good case can be made for obvious roadside attractions with easy access. After all, the classics of ski mountaineering live in the minds of the sport’s practitioners as much as they exist on the map. Thus, when a beautiful and easily reached snow-filled couloir stares us in the face as we drive to and from our work or play, it easily achieves “king line” status.

One such monarch is the Silver Couloir, on the north side of Buffalo Mountain near Silverthorne, Colorado. The line is easily spotted while driving Interstate 70 west from the Eisenhower Tunnel and can also be viewed from multiple locations on secondary roads in the area.

Reaching the top at sunrise is a bit early for the skiing, since the snow needs to soften a bit after getting a solid freeze. But witnessing the glorious orb’s daily debut provides a solace beyond mere climbing and skiing.

The wind is light and air temperature warm, so we easily relax and wait for the sun to slightly condition the snow in the couloir. The launch is easy, beginning with a rollover that gradually steepens and effortlessly funnels you to a narrower section between rock outcrops. I stay away from the rocks in case the snow is undermined and pump effortless turns on perfect snow. Pulling to the side below the rocks, I shout the “go” signal up to my partner, who easily locks his turns into the perfection of the snow surface, whooping a few times as he sprays sun-softened snow in a series of knife-perfect curves.

Soon positioned for the apron at the base of the couloir, we smile and nod at each other, then ski tandem figure eights to the bottom. We clack ski poles in a salute to the king and to mountain companionship, then traverse an irrigation ditch back to the summer trail.

Note: Lately the new generation of Gore explorers have been forcing many new routes on the more consequential couloirs that weave all over the north side of Buffalo. This mountain is seductive and complex and not without several incidents during the last decade. Be respectful of conditions and of under estimating whether a route goes or not.

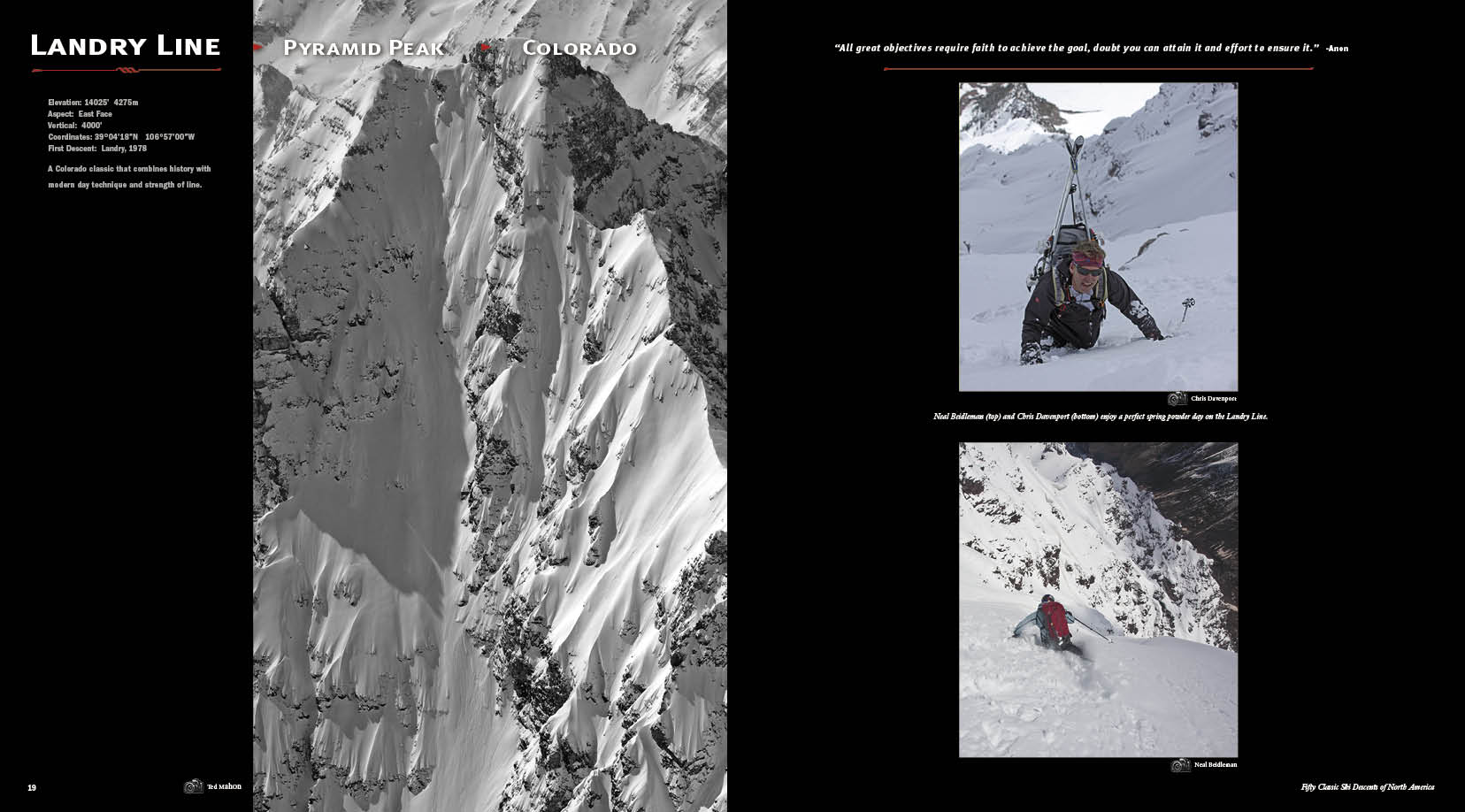

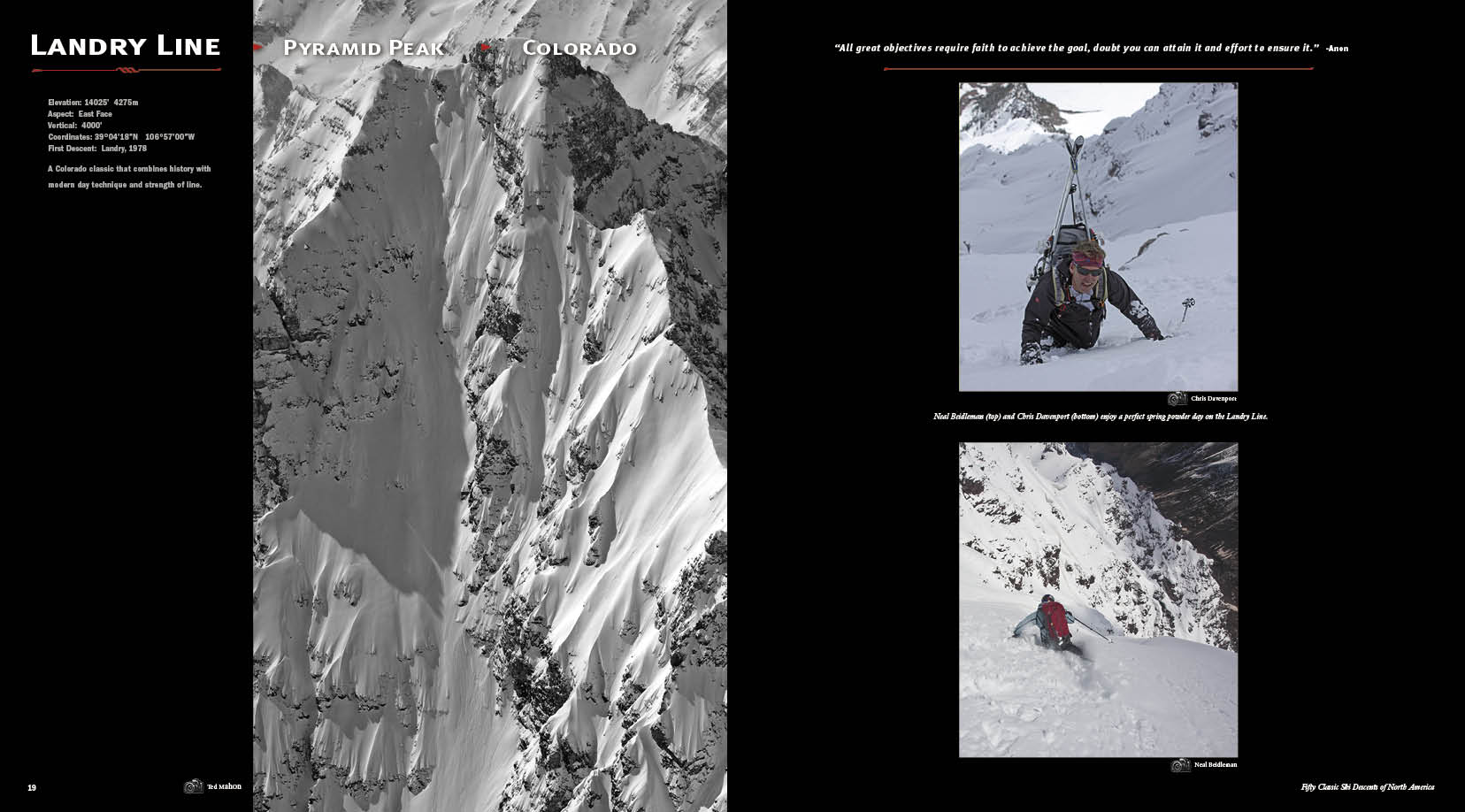

Chris Davenport

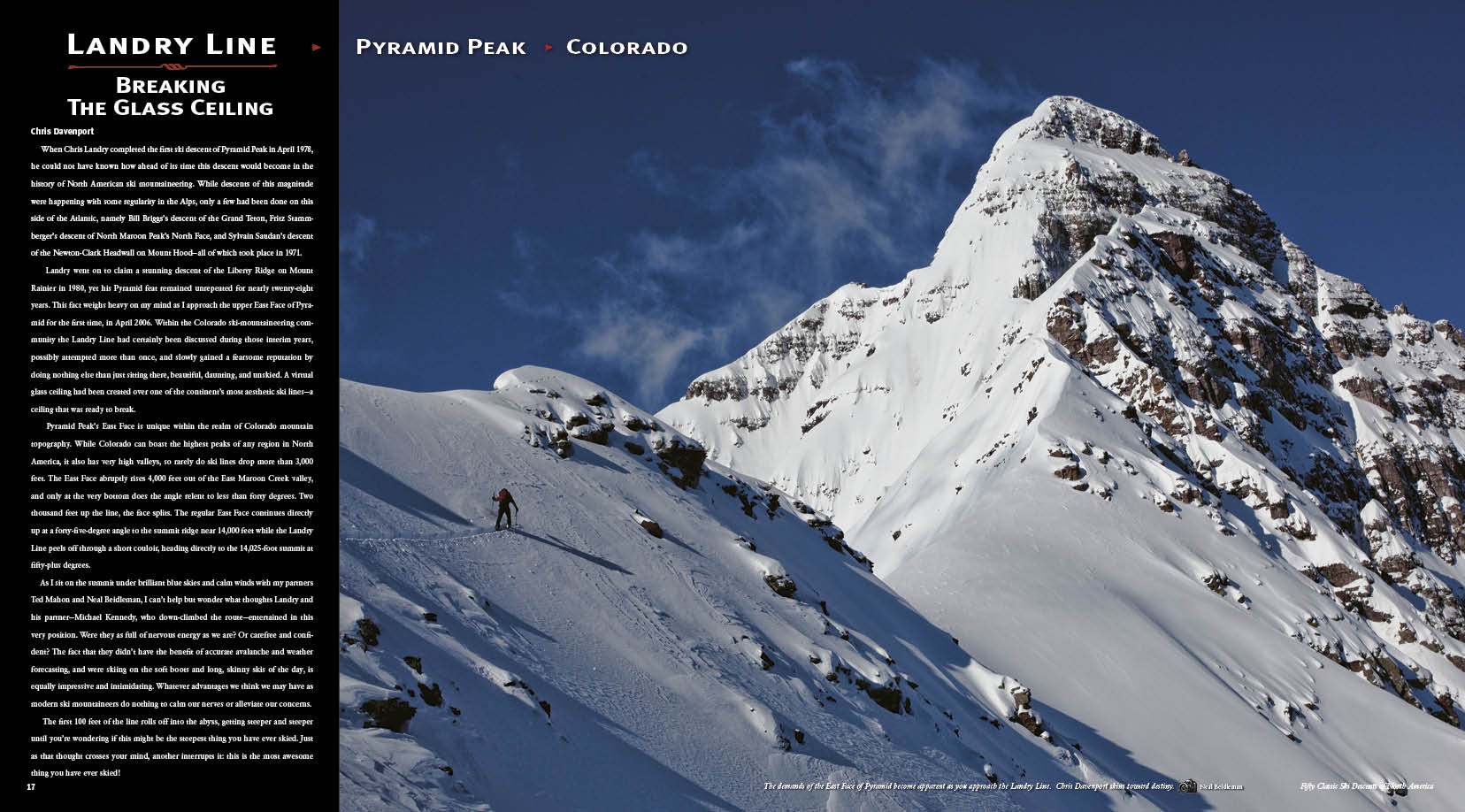

When Chris Landry completed the first ski descent of Pyramid Peak in April 1978, he could not have known how ahead of its time this descent would become in the history of North American ski mountaineering. While descents of this magnitude were happening with some regularity in the Alps, only a few had been done on this side of the Atlantic, namely Bill Briggs’s descent of the Grand Teton, Fritz Stammberger’s descent of North Maroon Peak’s North Face, and Sylvain Saudan’s descent of the Newton-Clark Headwall on Mount Hood—all of which took place in 1971.

Landry went on to claim a stunning descent of the Liberty Ridge on Mount Rainier in 1980, yet his Pyramid feat remained unrepeated for nearly twenty-eight years. This fact weighs heavy on my mind as I approach the upper East Face of Pyramid for the first time, in April 2006. Within the Colorado ski-mountaineering community the Landry Line had certainly been discussed during those interim years, possibly attempted more than once, and slowly gained a fearsome reputation by doing nothing else than just sitting there, beautiful, daunting, and unskied. A virtual glass ceiling had been created over one of the continent’s most aesthetic ski lines—a ceiling that was ready to break.

Pyramid Peak’s East Face is unique within the realm of Colorado mountain topography. While Colorado can boast the highest peaks of any region in North America, it also has very high valleys, so rarely do ski lines drop more than 3,000 feet. The East Face abruptly rises 4,000 feet out of the East Maroon Creek valley, and only at the very bottom does the angle relent to less than forty degrees. Two thousand feet up the line, the face splits. The regular East Face continues directly up at a forty-five-degree angle to the summit ridge near 14,000 feet while the Landry Line peels off through a short couloir, heading directly to the 14,025-foot summit at fifty-plus degrees.

As I sit on the summit under brilliant blue skies and calm winds with my partners Ted Mahon and Neal Beidleman, I can’t help but wonder what thoughts Landry and his partner—Michael Kennedy, who down-climbed the route—entertained in this very position. Were they as full of nervous energy as we are? Or carefree and confident? The fact that they didn’t have the benefit of accurate avalanche and weather forecasting, and were skiing on the soft boots and long, skinny skis of the day, is equally impressive and intimidating. Whatever advantages we think we may have as modern ski mountaineers does nothing to calm our nerves or alleviate our concerns.

The first 100 feet of the line rolls off into the abyss, getting steeper and steeper until you’re wondering if this might be the steepest thing you have ever skied. Just as that thought crosses your mind, another interrupts it: this is the most awesome thing you have ever skied!