Here is a sampling of the Canadian section. To see every section and detailed interviews purchase the book here on the official website.

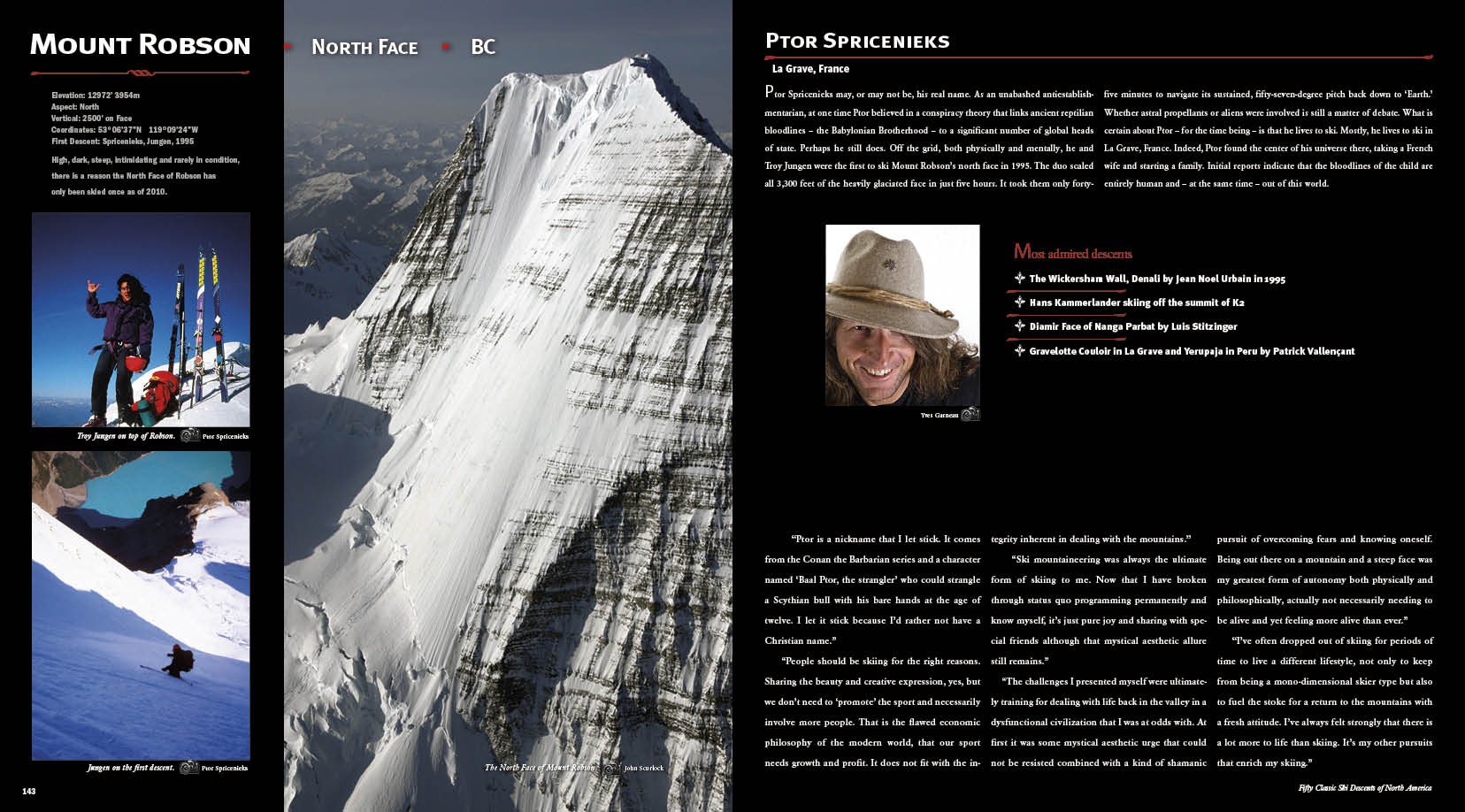

"On the drive there I am drawn by the mountain’s power, feeling helpless yet entranced by our inescapable commitment. It’s almost like I am surrendering my life to the mountain for its own purpose and some unknown destiny." -Ptor Spricenieks

A lofty goal during anytime of the year, Robson has turned back the most ambitious and the most committed. Weather, ice, crevasse and an immensely complex 10,000' face will challenge the best in the world. Here is a telling excerpt from the first descent by Ptor Spricenieks and Troy Jungen.

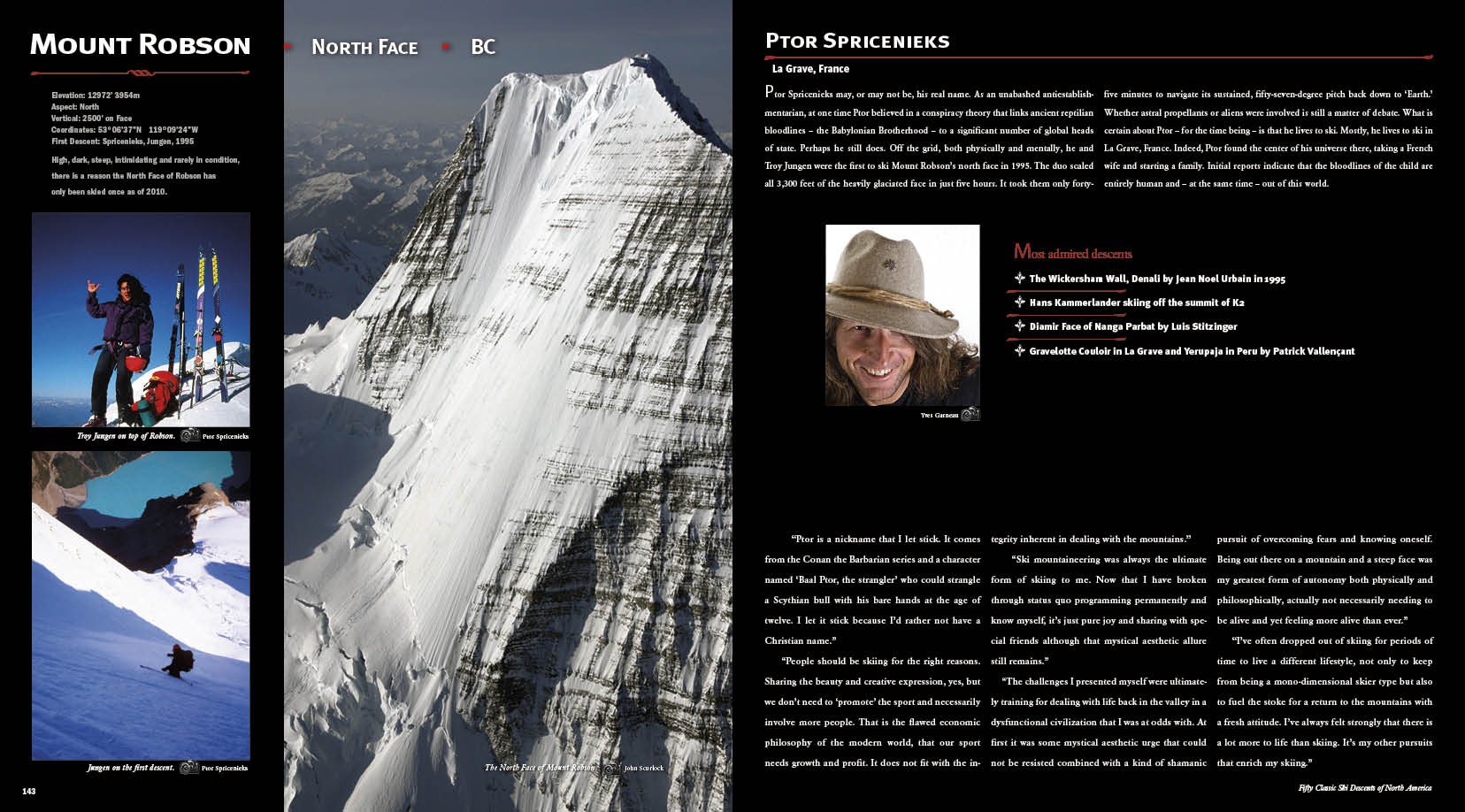

Ptor Spricenieks - Yuh-hai-has-kun (YHHK) is the original Shuswap name for Mount Robson, meaning ‘Mountain of the Spiral Road.’ As the King of the Rockies, it always seemed more fitting and respectful for it to be called by its traditional name rather than after some colonialist fur trapper who never climbed it. For Troy Jungen and me, it was always the ultimate steep ski descent, a truly wild and mystical grail deemed impossible, a line that ventured into the unknown.

Troy is the main instigator of this adventure, having monitored conditions all summer while I was away at Nanga Parbat in Pakistan. Surely there is no one else who could have created the crucial combination of confidence and higher purpose for myself with such an undertaking.

On the drive there I am drawn by the mountain’s power, feeling helpless yet entranced by our inescapable commitment. It’s almost like I am surrendering my life to the mountain for its own purpose and some unknown destiny.... read more in Fifty Classic Ski Descents which on our purchase page.

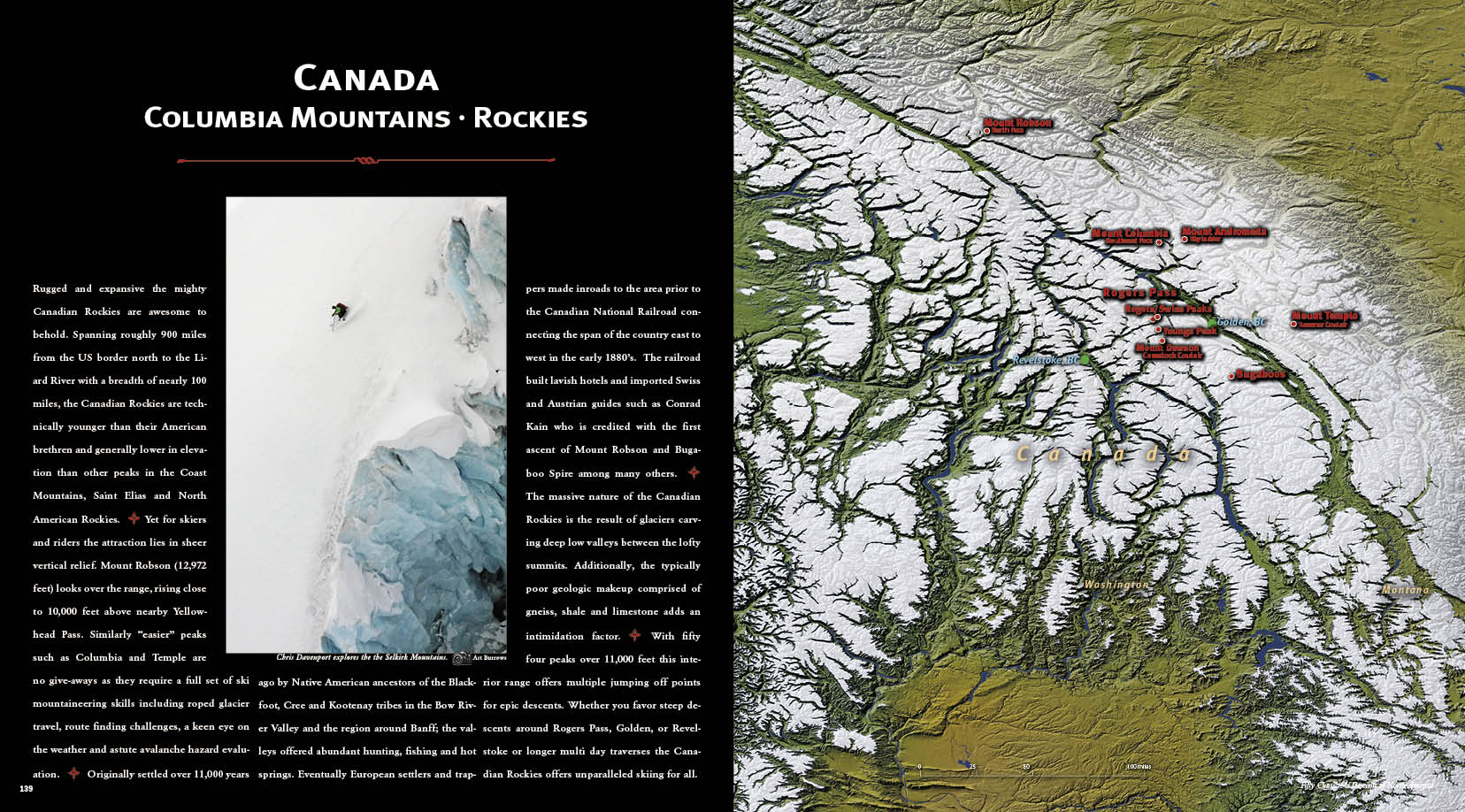

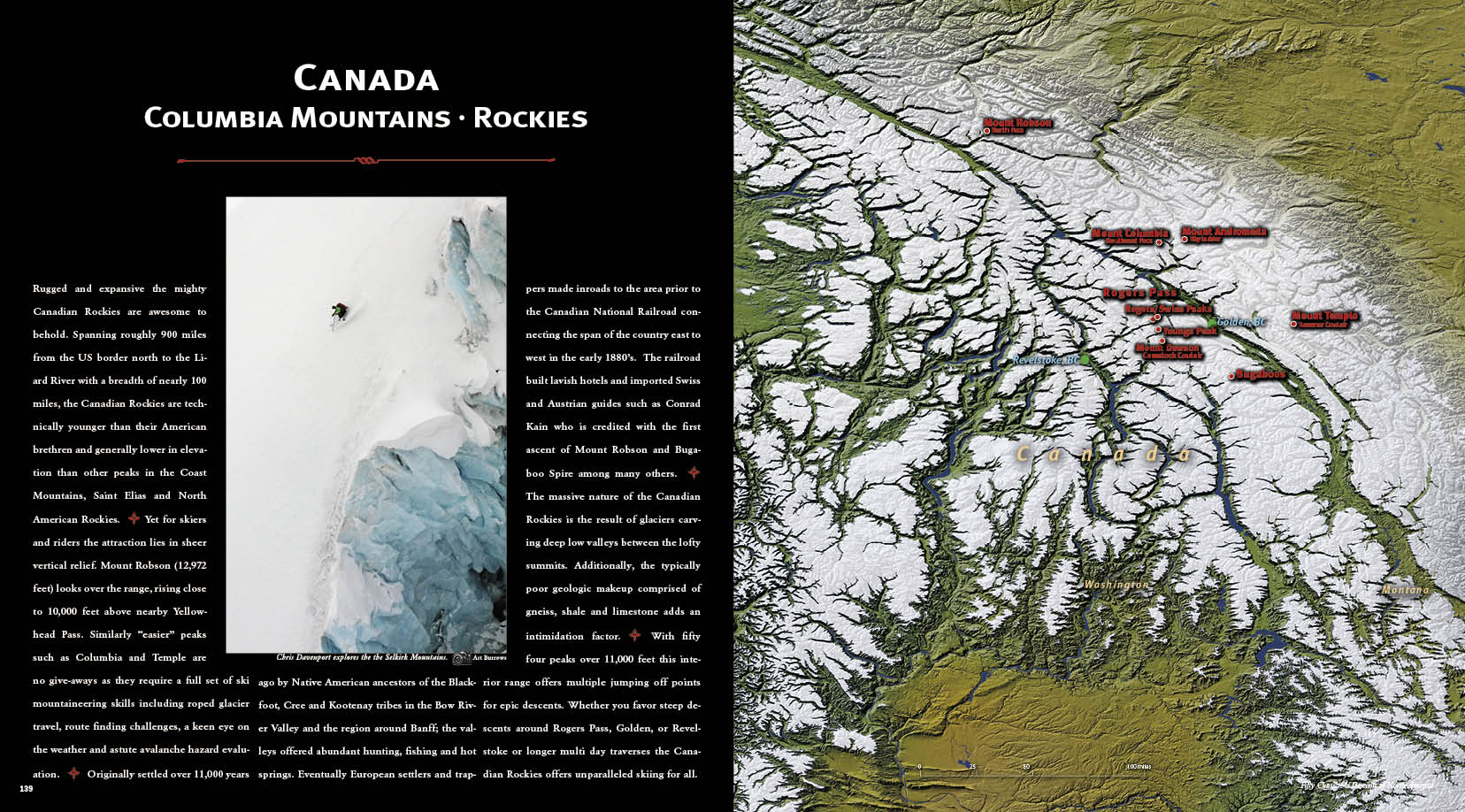

Rugged and expansive the mighty interior zones of the Canadian Rockies are awesome to behold. Spanning roughly 900 miles from the US border north to the Liard River with a breadth of nearly 100 miles, the Canadian Rockies are technically younger than their American brethren and generally lower in elevation than other peaks in the Coast Mountains, Saint Elias and North American Rockies. • Yet for skiers and riders the attraction lies in sheer vertical relief. Mount Robson (12,972 feet) looks over the range, rising close to 10,000 feet above nearby Yellowhead Pass. Similarly “easier” peaks such as Columbia and Temple are no give-aways as they require a full set of ski mountaineering skills including roped glacier travel, route finding challenges, a keen eye on the weather and astute avalanche hazard evaluation. • Originally settled over 11,000 years ago by Native American ancestors of the Blackfoot, Cree and Kootenay tribes in the Bow River Valley and the region around Banff; the valleys offered abundant hunting, fishing and hot springs. Eventually European settlers and trappers made inroads to the area prior to the Canadian National Railroad connecting the span of the country east to west in the early 1880’s. The railroad built lavish hotels and imported Swiss and Austrian guides such as Conrad Kain who is credited with the first ascent of Mount Robson and Bugaboo Spire among many others. • The massive nature of the Canadian Rockies is the result of glaciers carving deep low valleys between the lofty summits. Additionally, the typically poor geologic makeup comprised of gneiss, shale and limestone adds an intimidation factor. • With fifty four peaks over 11,000 feet this interior range offers multiple jumping off points for epic descents. Whether you favor steep descents around Rogers Pass, Golden, or Revelstoke or longer multi day traverses the Canadian Rockies offers unparalleled skiing for all.

Difficult to get in good weather but if you're there at the right time, a definite classic.

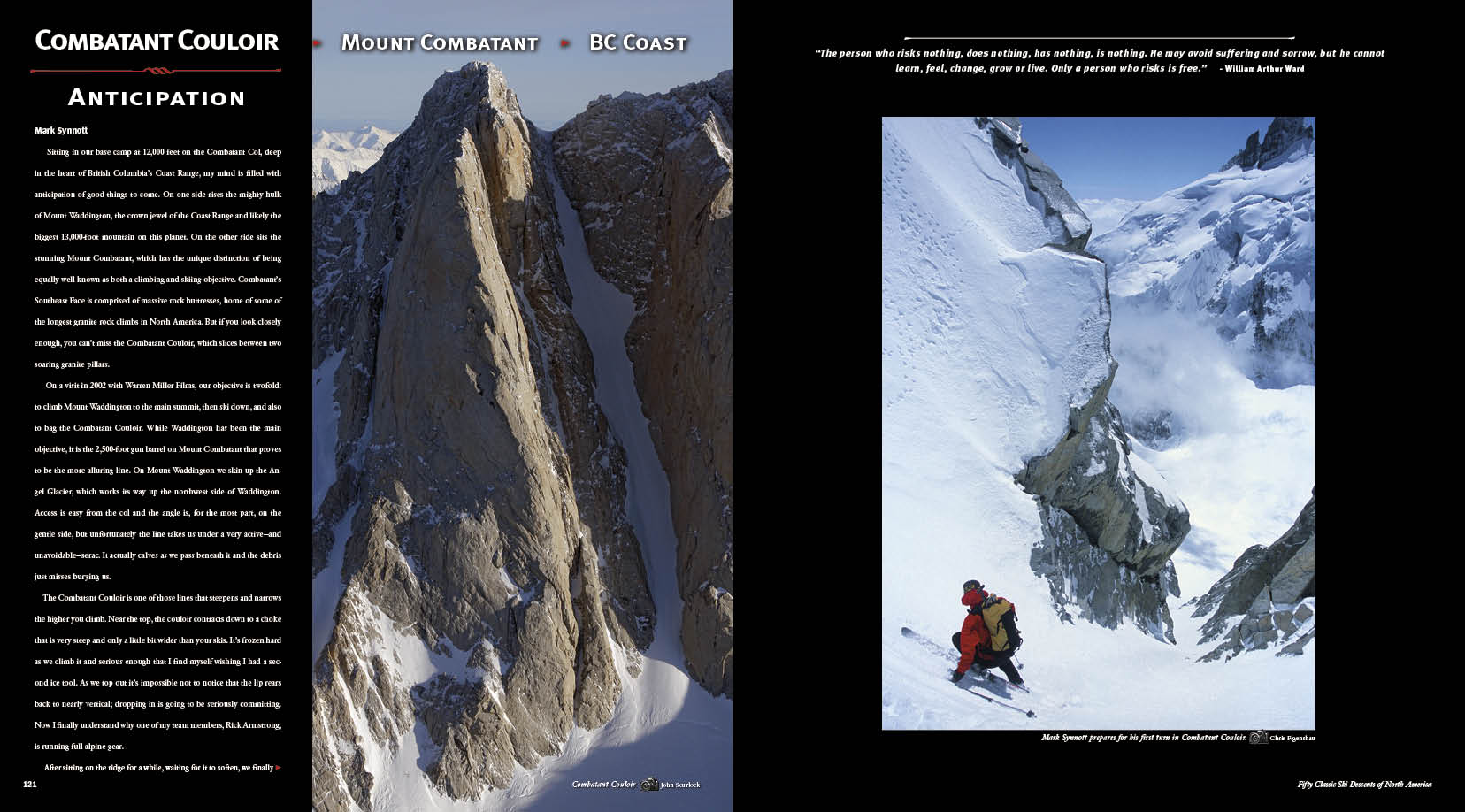

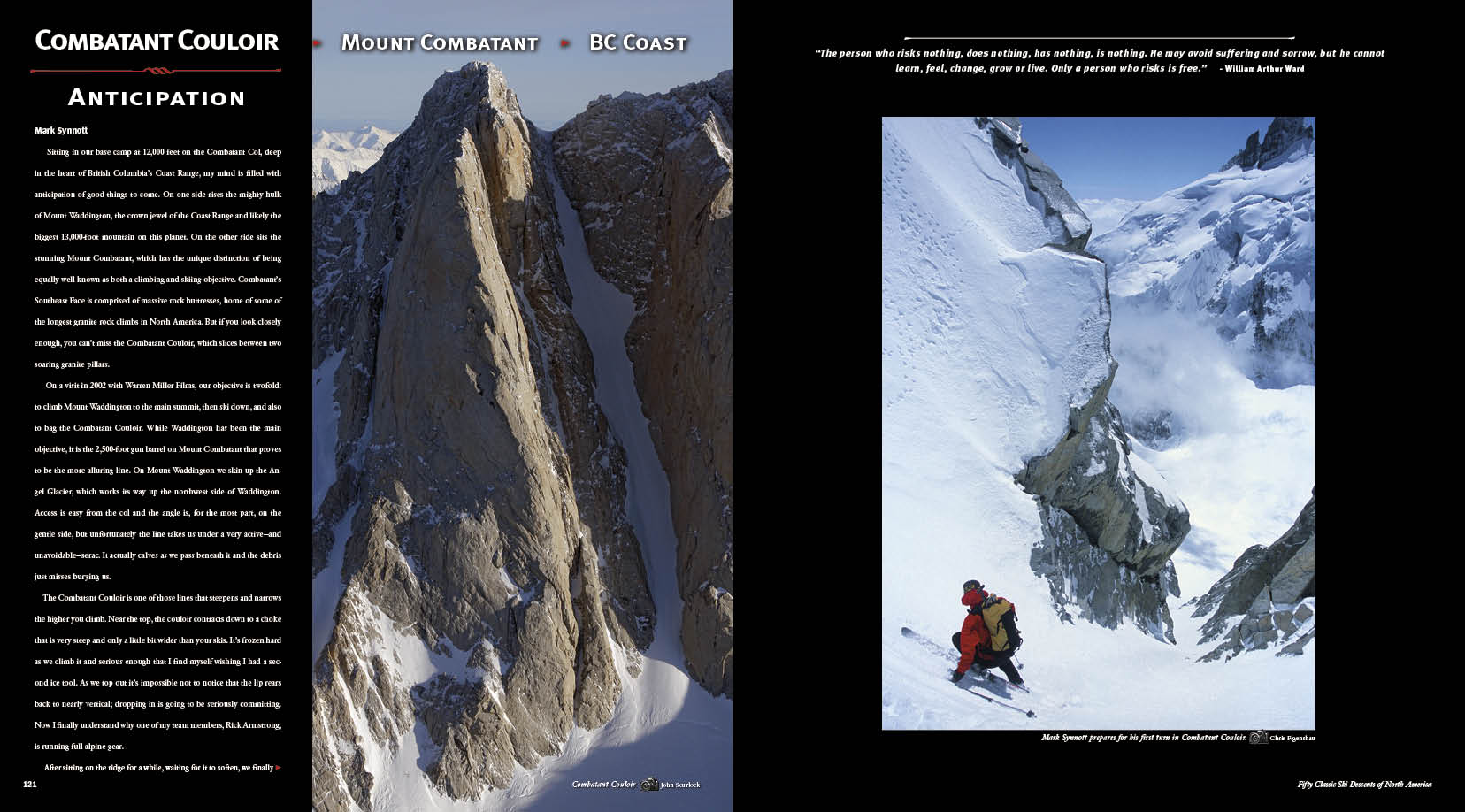

Mark Synnott - Sitting in our base camp at 12,000 feet on the Combatant Col, deep in the heart of British Columbia’s Coast Range, my mind is filled with anticipation of good things to come. On one side rises the mighty hulk of Mount Waddington, the crown jewel of the Coast Range and likely the biggest 13,000-foot mountain on this planet. On the other side sits the stunning Mount Combatant, which has the unique distinction of being equally well known as both a climbing and skiing objective. Combatant’s Southeast Face is comprised of massive rock buttresses, home of some of the longest granite rock climbs in North America. But if you look closely enough, you can’t miss the Combatant Couloir, which slices between two soaring granite pillars.

On a visit in 2002 with Warren Miller Films, our objective is twofold: to climb Mount Waddington to the main summit, then ski down, and also to bag the Combatant Couloir. While Waddington has been the main objective, it is the 2,500-foot gun barrel on Mount Combatant that proves to be the more alluring line. On Mount Waddington we skin up the Angel Glacier, which works its way up the northwest side of Waddington. Access is easy from the col and the angle is, for the most part, on the gentle side, but unfortunately the line takes us under a very active—and unavoidable—serac. It actually calves as we pass beneath it and the debris just misses burying us.

The Combatant Couloir is one of those lines that steepens and narrows the higher you climb. Near the top, the couloir contracts down to a choke that is very steep and only a little bit wider than your skis. It’s frozen hard as we climb it and serious enough that I find myself wishing I had a second ice tool. As we top out it’s impossible not to notice that the lip rears back to nearly vertical; dropping in is going to be seriously committing. Now I finally understand why one of my team members, Rick Armstrong, is running full alpine gear.

After sitting on the ridge for a while, waiting for it to soften, we finally

accept that the top part of the couloir is not going to corn. My partners start to gear up, but I am still a little iffy, especially after Rick shares with me what he thinks will happen if you fall dropping in. I put my pack on and start down-climbing, hoping to find a spot farther down to get my skis on. I descend about fifty feet, then stop and look down the slope from the skier’s perspective. That’s when I know in my heart that I can ski it. I turn around and head back up. As I pop back over the ridge, my friends greet me with an approving cheer.

Dropping in is definitely the crux, but the reward is 2,500 feet of some of the best couloir skiing on the continent. The line follows a single fall line from top to bottom and the couloir broadens and lessens in angle as you descend, so you can open it up more and more. Perhaps the best part is jumping the ’schrund and then slicing through fresh corn straight back into camp.

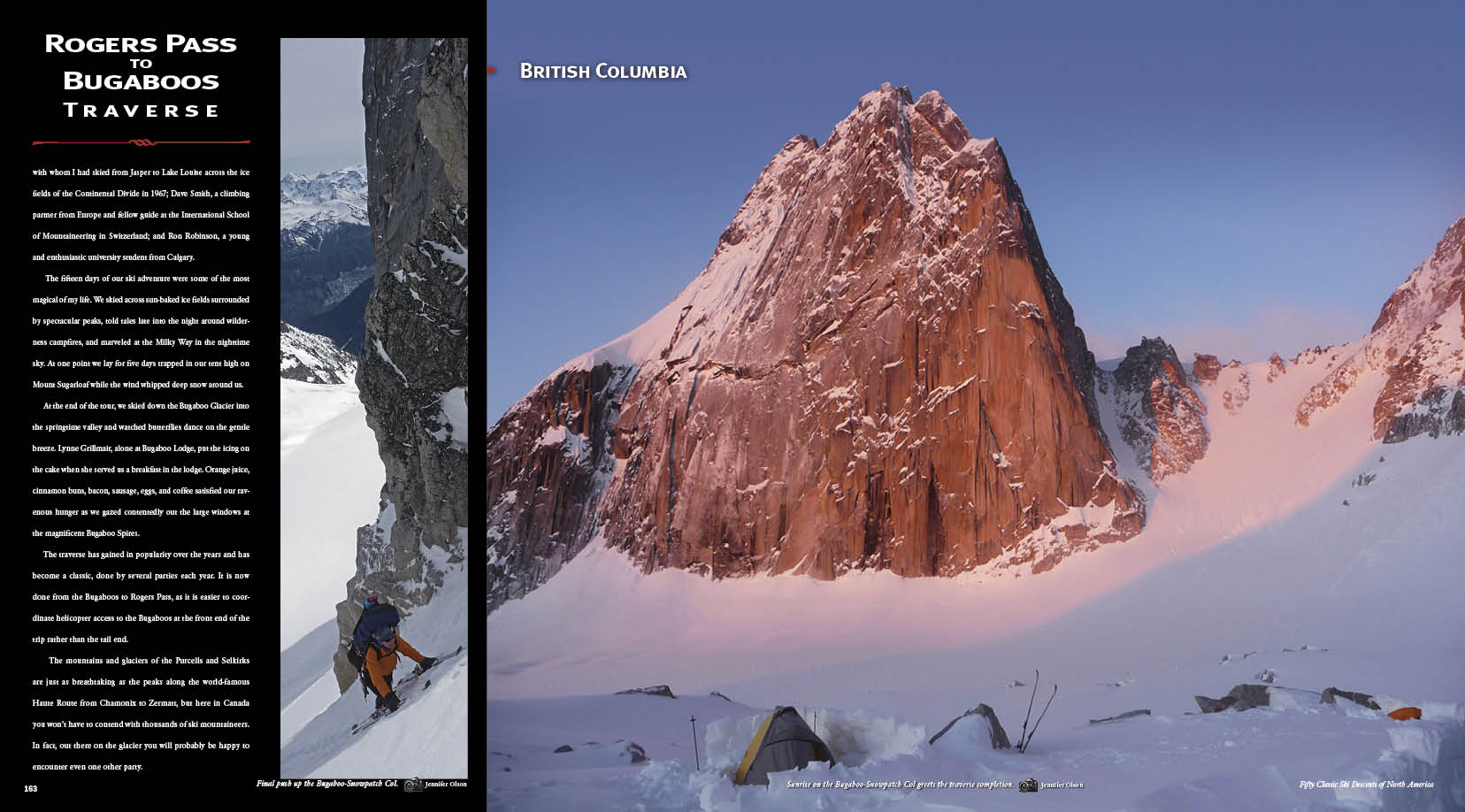

Note: The original traverse in 1958 by Bill Briggs Barry Corbet, Bob French and Sterling Neal traversed from the Bugaboos to Rogers Pass. At the time you couldn’t get useful maps of this area of Canada, and only one hut provided shelter along the way. To top that, no expeditions of this sort, using skis on technical glaciers and passes, had been attempted in North America. Briggs knew of Fridtjof Nansen’s well publicized traverse of Greenland in 1888, and wanted to show North America what a terrific tool skis were for mountaineering. “There was something to be said,” he remembers in a moment of philosophical reflection. Briggs seem to know it best to descend on the norths and ascend in the mornings on the souths. In contrast Chic Scott's Los Desparados navigated from Rogers Pass to the Bugaboos. However in my experience its best to begin in the Bugs and ski north to Rogers Pass. Why? the descents are more likely to have good snow on the north facing descents (better with a big pack) and the ascents are quicker and safer if your timing is good on the frozen south faces. Either way this is a once in a lifetime opportunity to see a phenomenal passage though two of Canada's most beautiful ranges during a nearly 100 mile tour of 10 days. Do it slowly and enjoy a few descents along the way if you have the time. Route finding is difficult and a bit sketchy in the famous Canadian clagg so be ready for any weather on this one. -Art Burrows w/ Briggs research by Lou Dawson

Chic Scott

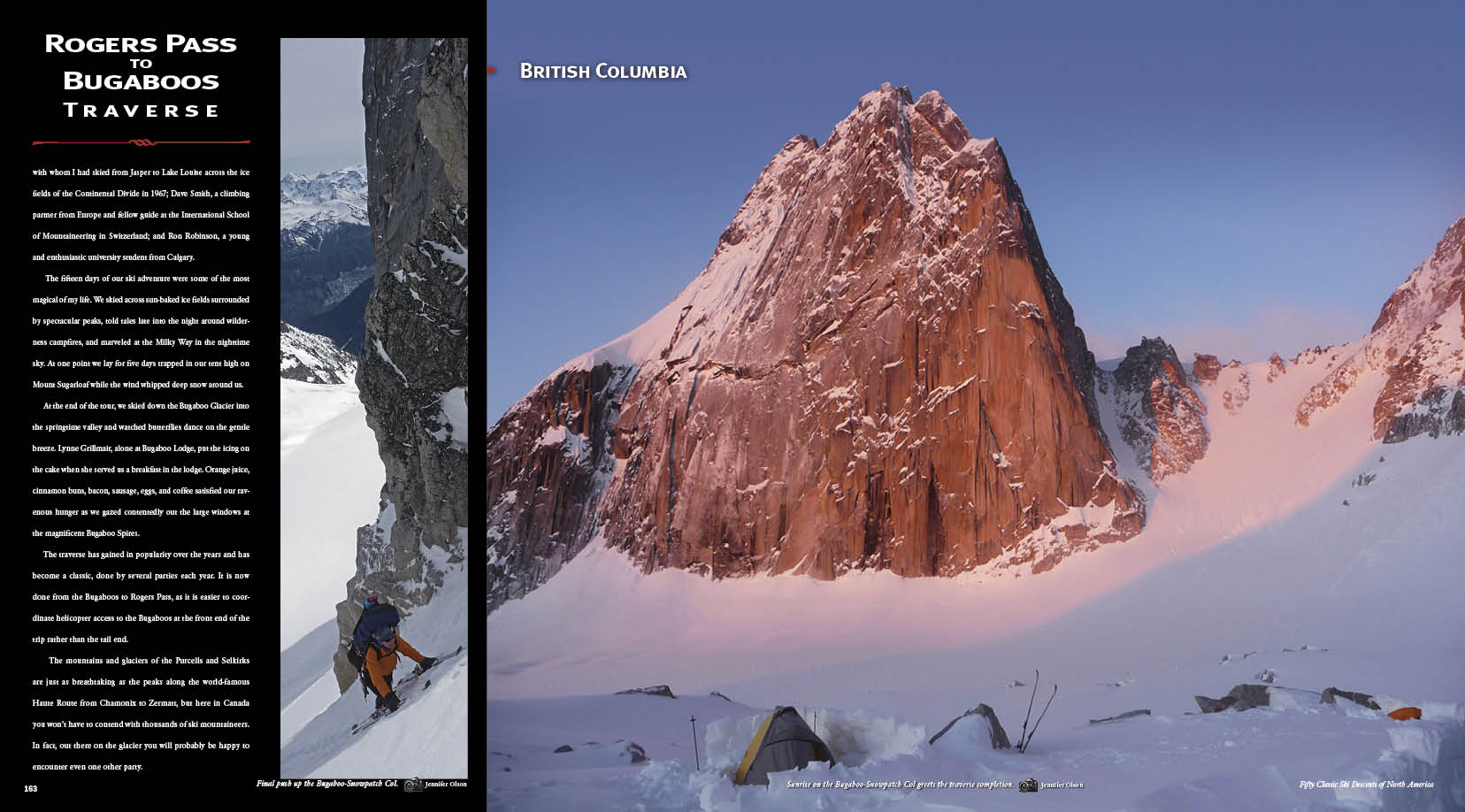

Nineteen seventy-three was my best year as a mountaineer. I climbed four north faces in the European Alps and narrowly missed the first ascent of a 25,000-foot summit in the Nepal Himalaya. But perhaps the most memorable experience of that year was an 80-mile ski traverse in May from Rogers Pass to the Bugaboos, across the glaciers and ice fields of the Selkirk and Purcell ranges.

We were not the first to ski the route. It had been traversed in June of 1958 by four young men from Dartmouth University: Bill Briggs, Barry Corbet, Sterling Neale, and Bob French.

They had written a brief account of their adventure in The Canadian Alpine Journal, and when I read it I wanted to repeat their journey. It gave me something to dream about during the long winter months while I worked the Strawberry T-bar at Sunshine Village Ski Resort.

We were four on the traverse: joining me were Don Gardner, • with whom I had skied from Jasper to Lake Louise across the ice fields of the Continental Divide in 1967; Dave Smith, a climbing partner from Europe and fellow guide at the International School of Mountaineering in Switzerland; and Ron Robinson, a young and enthusiastic university student from Calgary.

The fifteen days of our ski adventure were some of the most magical of my life. We skied across sun-baked ice fields surrounded by spectacular peaks, told tales late into the night around wilderness campfires, and marveled at the Milky Way in the nighttime sky. At one point we lay for five days trapped in our tent high on Mount Sugarloaf while the wind whipped deep snow around us.

At the end of the tour, we skied down the Bugaboo Glacier into the springtime valley and watched butterflies dance on the gentle breeze. Lynne Grillmair, alone at Bugaboo Lodge, put the icing on the cake when she served us a breakfast in the lodge. Orange juice, cinnamon buns, bacon, sausage, eggs, and coffee satisfied our ravenous hunger as we gazed contentedly out the large windows at the magnificent Bugaboo Spires.

The traverse has gained in popularity over the years and has become a classic, done by several parties each year. It is now done from the Bugaboos to Rogers Pass, as it is easier to coordinate helicopter access to the Bugaboos at the front end of the trip rather than the tail end.

The mountains and glaciers of the Purcells and Selkirks are just as breathtaking as the peaks along the world-famous Haute Route from Chamonix to Zermatt, but here in Canada you won’t have to contend with thousands of ski mountaineers. In fact, out there on the glacier you will probably be happy to encounter even one other party.

An iconic location and not a gimme. Listen up folks and learn about traveling across this glacial landscape.

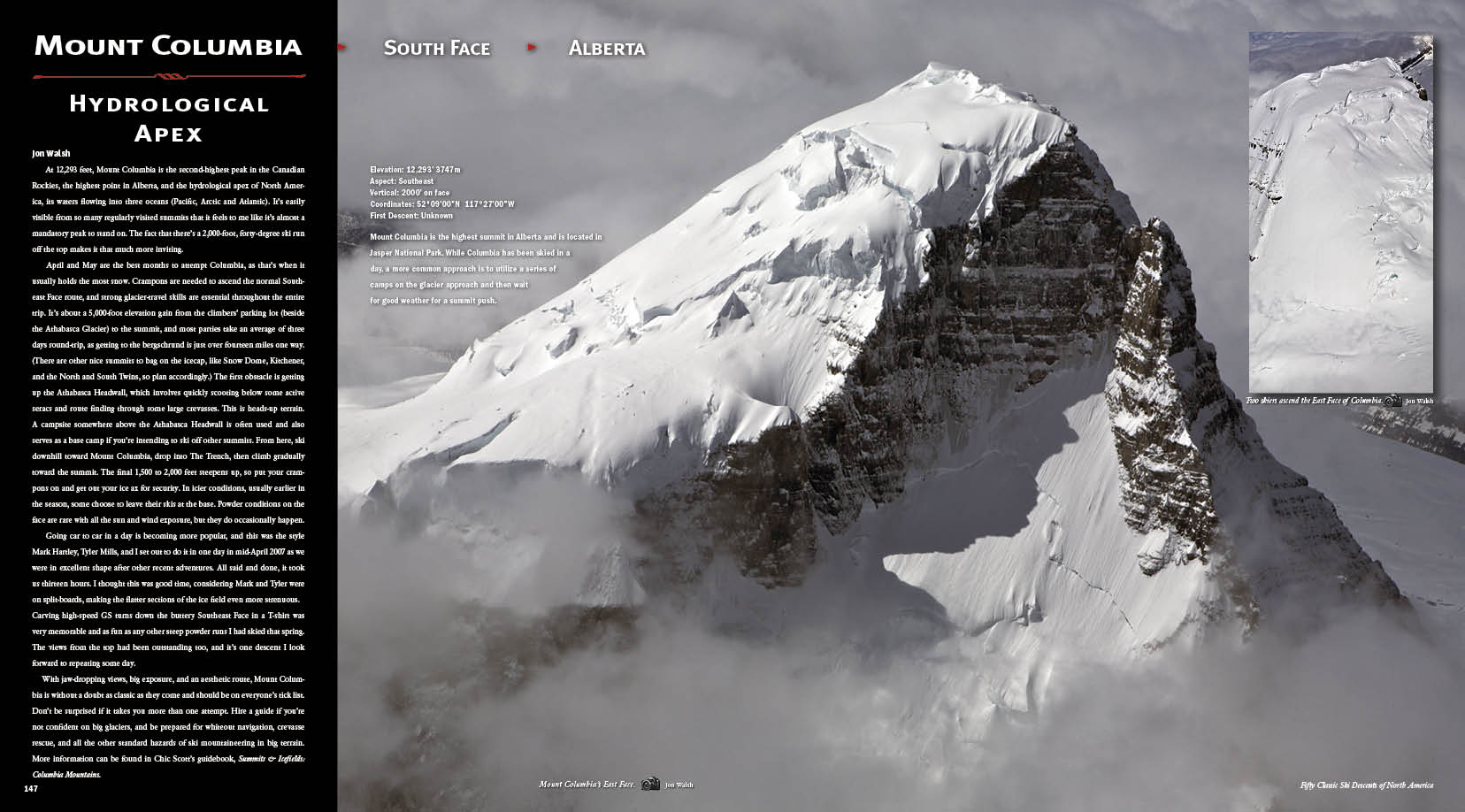

Jon Walsh - 2009

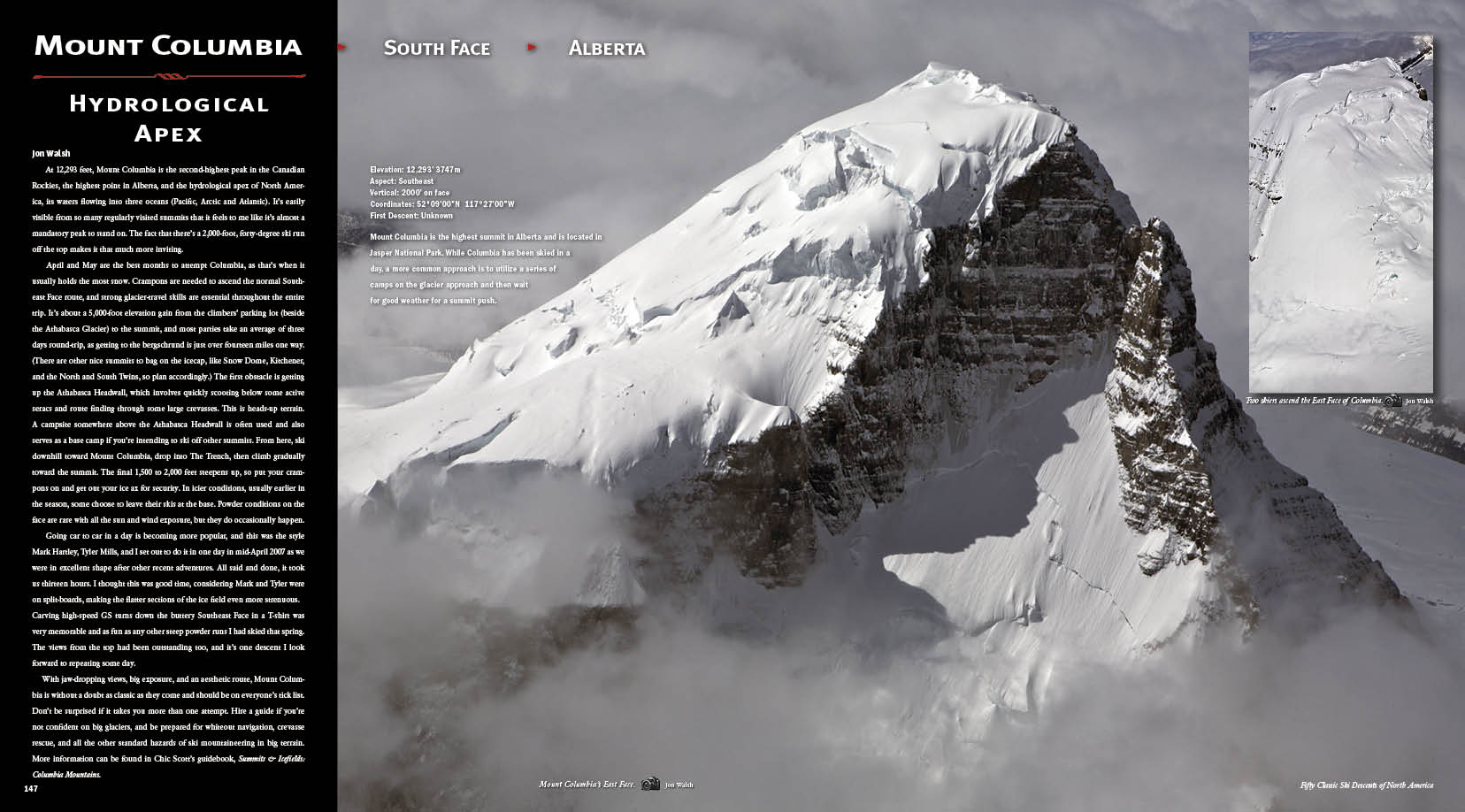

At 12,293 feet, Mount Columbia is the second-highest peak in the Canadian Rockies, the highest point in Alberta, and the hydrological apex of North America, its waters flowing into three oceans (Pacific, Arctic and Atlantic). It’s easily visible from so many regularly visited summits that it feels to me like it’s almost a mandatory peak to stand on. The fact that there’s a 2,000-foot, forty-degree ski run off the top makes it that much more inviting.

April and May are the best months to attempt Columbia, as that’s when it usually holds the most snow. Crampons are needed to ascend the normal Southeast Face route, and strong glacier-travel skills are essential throughout the entire trip. It’s about a 5,000-foot elevation gain from the climbers’ parking lot (beside the Athabasca Glacier) to the summit, and most parties take an average of three days round-trip, as getting to the bergschrund is just over fourteen miles one way. (There are other nice summits to bag on the icecap, like Snow Dome, Kitchener, and the North and South Twins, so plan accordingly.) The first obstacle is getting up the Athabasca Headwall, which involves quickly scooting below some active seracs and route finding through some large crevasses. This is heads-up terrain.

A campsite somewhere above the Athabasca Headwall is often used and also serves as a base camp if you’re intending to ski off other summits. From here, ski downhill toward Mount Columbia, drop into The Trench, then climb gradually toward the summit. The final 1,500 to 2,000 feet steepens up, so put your crampons on and get out your ice ax for security. In icier conditions, usually earlier in the season, some choose to leave their skis at the base. Powder conditions on the face are rare with all the sun and wind exposure, but they do occasionally happen.

Going car to car in a day is becoming more popular, and this was the style Mark Hartley, Tyler Mills, and I set out to do it in one day in mid-April 2007 as we were in excellent shape after other recent adventures. All said and done, it took us thirteen hours. I thought this was good time, considering Mark and Tyler were on split-boards, making the flatter sections of the ice field even more strenuous.

Carving high-speed GS turns down the buttery Southeast Face in a T-shirt was very memorable and as fun as any other steep powder runs I had skied that spring. The views from the top had been outstanding too, and it’s one descent I look forward to repeating some day.

With jaw-dropping views, big exposure, and an aesthetic route, Mount Columbia is without a doubt as classic as they come and should be on everyone’s tick list. Don’t be surprised if it takes you more than one attempt. Hire a guide if you’re not confident on big glaciers, and be prepared for whiteout navigation, crevasse rescue, and all the other standard hazards of ski mountaineering in big terrain. More information can be found in Chic Scott’s guidebook, Summits & Icefields: Columbia Mountains.

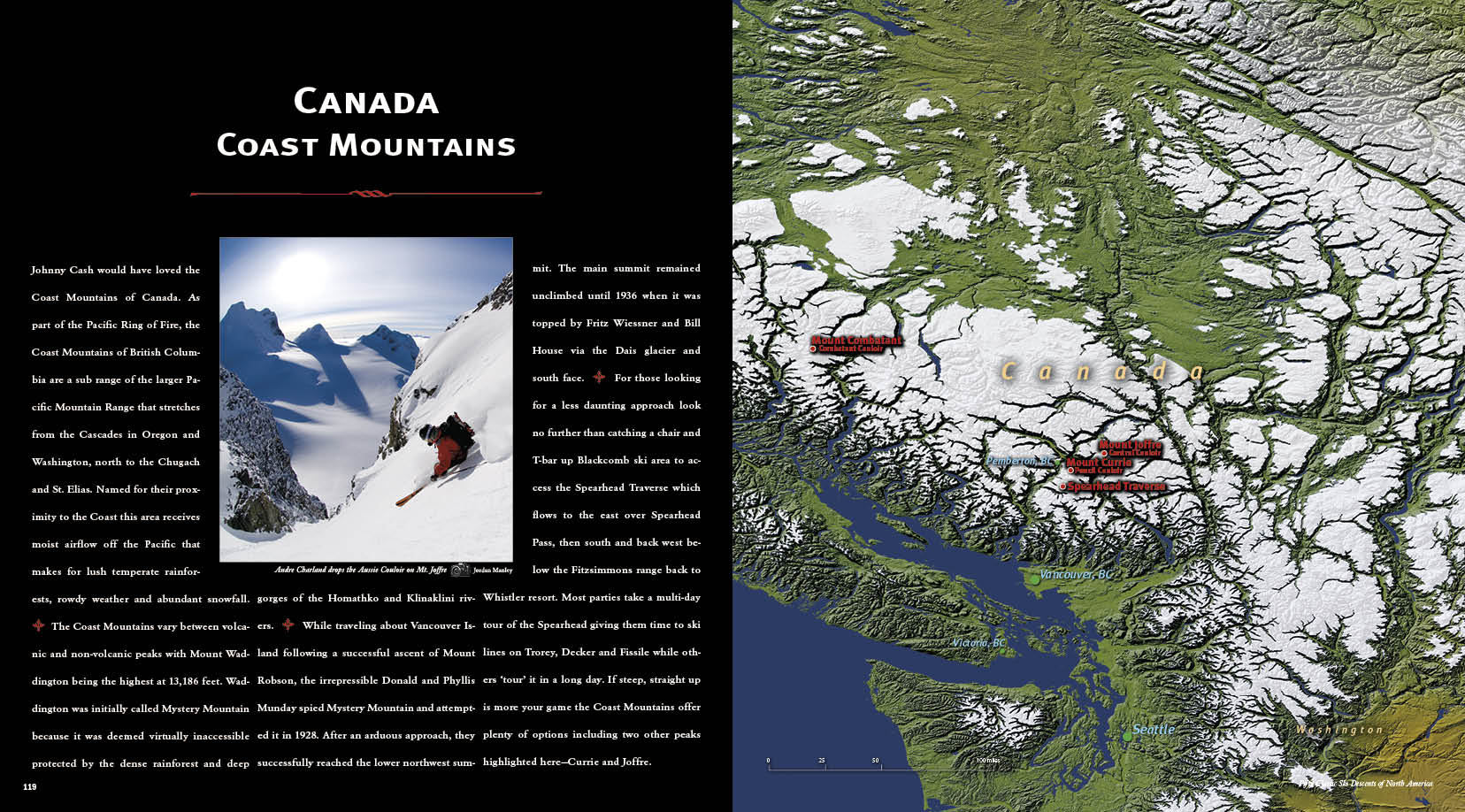

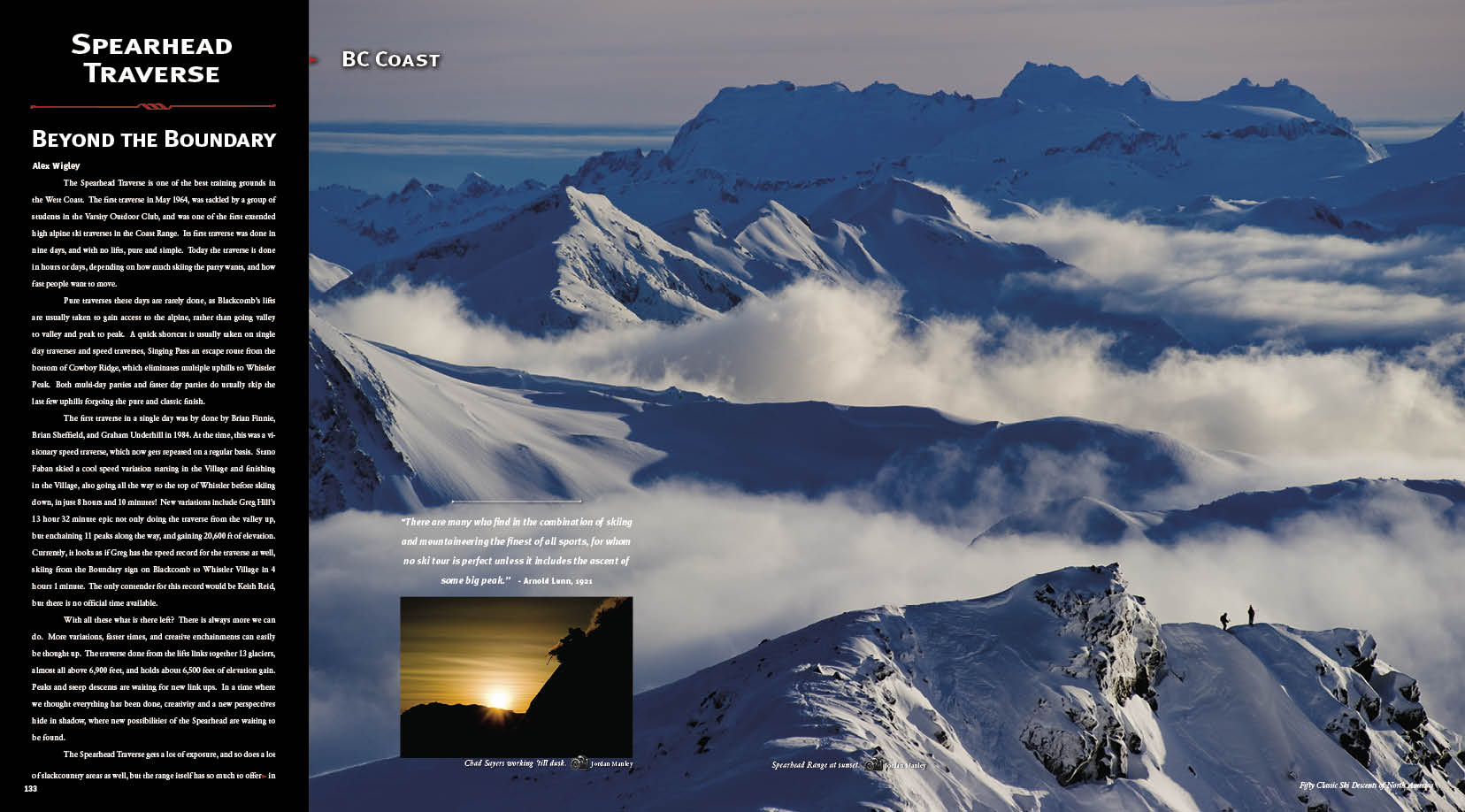

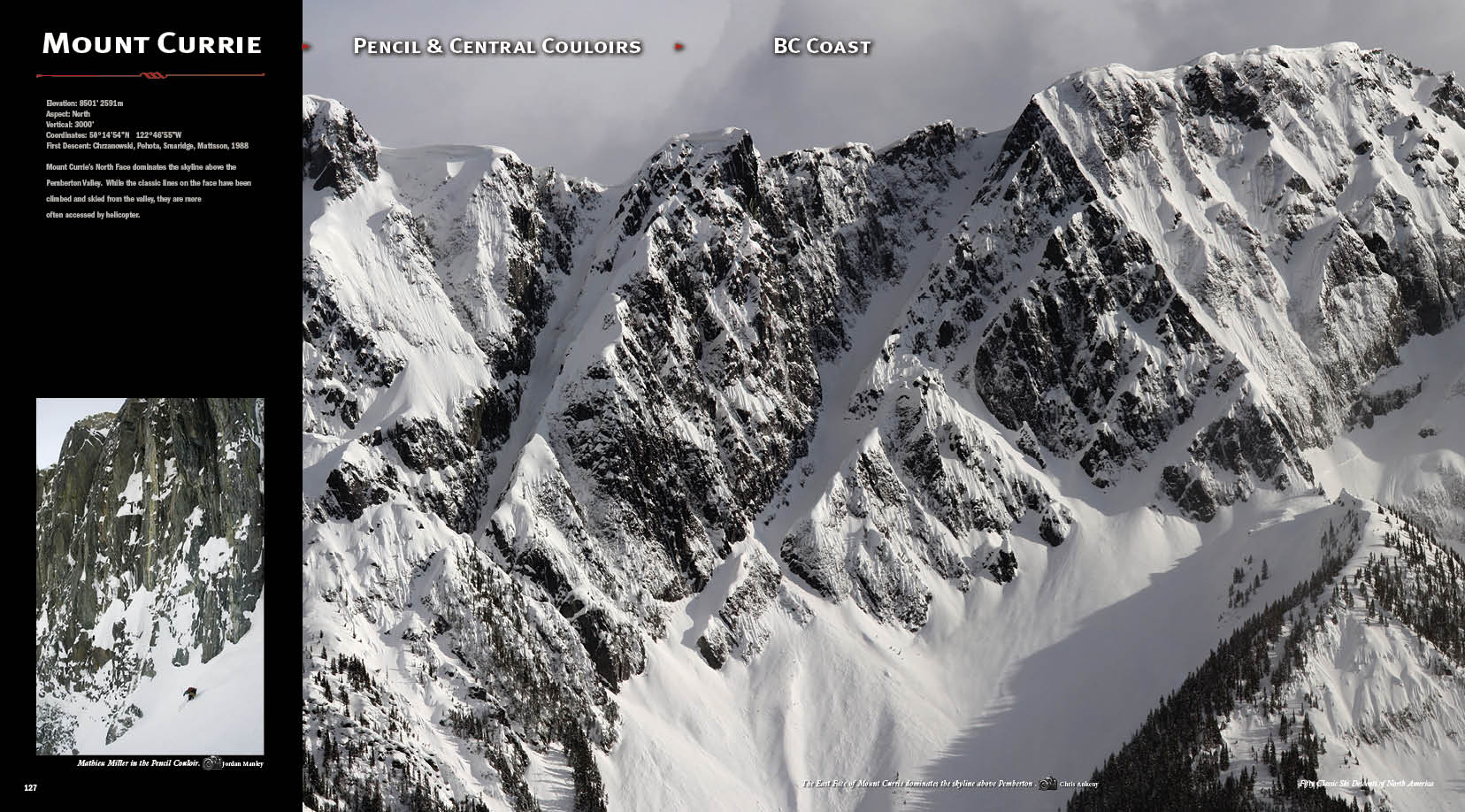

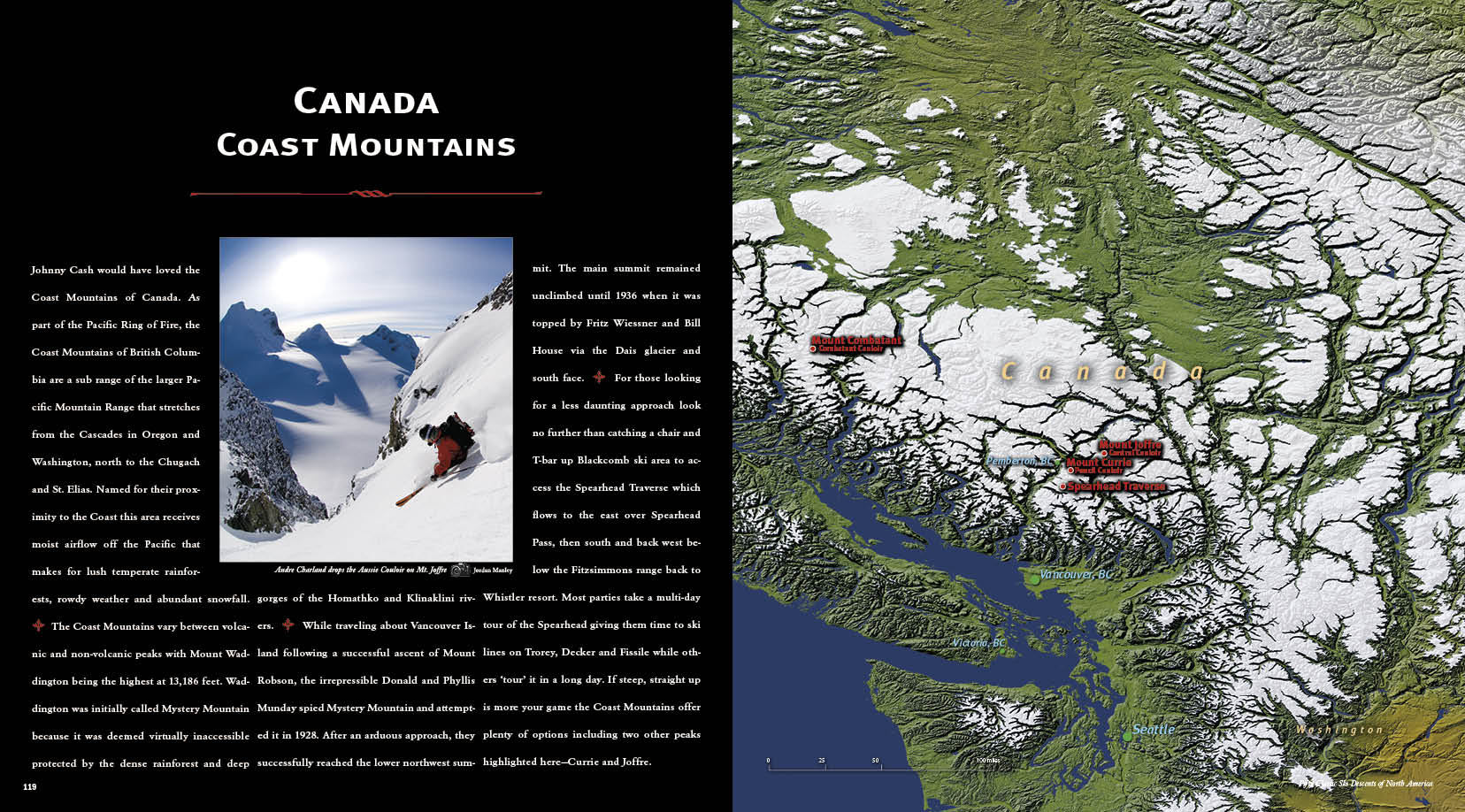

Johnny Cash would have loved the Coast Mountains of Canada. As part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Coast Mountains of British Columbia are a sub range of the larger Pacific Mountain Range that stretches from the Cascades in Oregon and Washington, north to the Chugach and St. Elias. Named for their proximity to the Coast this area receives moist airflow off the Pacific that makes for lush temperate rainforests, rowdy weather and abundant snowfall. y The Coast Mountains vary between volcanic and non-volcanic peaks with Mount Waddington being the highest at 13,186 feet. Waddington was initially called Mystery Mountain because it was deemed virtually inaccessible protected by the dense rainforest and deep gorges of the Homathko and Klinaklini rivers. y While traveling about Vancouver Island following a successful ascent of Mount Robson, the irrepressible Donald and Phyllis Munday spied Mystery Mountain and attempted it in 1928. After an arduous approach, they successfully reached the lower northwest summit. The main summit remained unclimbed until 1936 when it was topped by Fritz Wiessner and Bill House via the Dais glacier and south face. y For those looking for a less daunting approach look no further than catching a chair and T-bar up Blackcomb ski area to access the Spearhead Traverse which flows to the east over Spearhead Pass, then south and back west below the Fitzsimmons range back to Whistler resort. Most parties take a multi-day tour of the Spearhead giving them time to ski lines on Trorey, Decker and Fissile while others ‘tour’ it in a long day. If steep, straight up is more your game the Coast Mountains offer plenty of options including two other peaks highlighted here—Currie and Joffre.

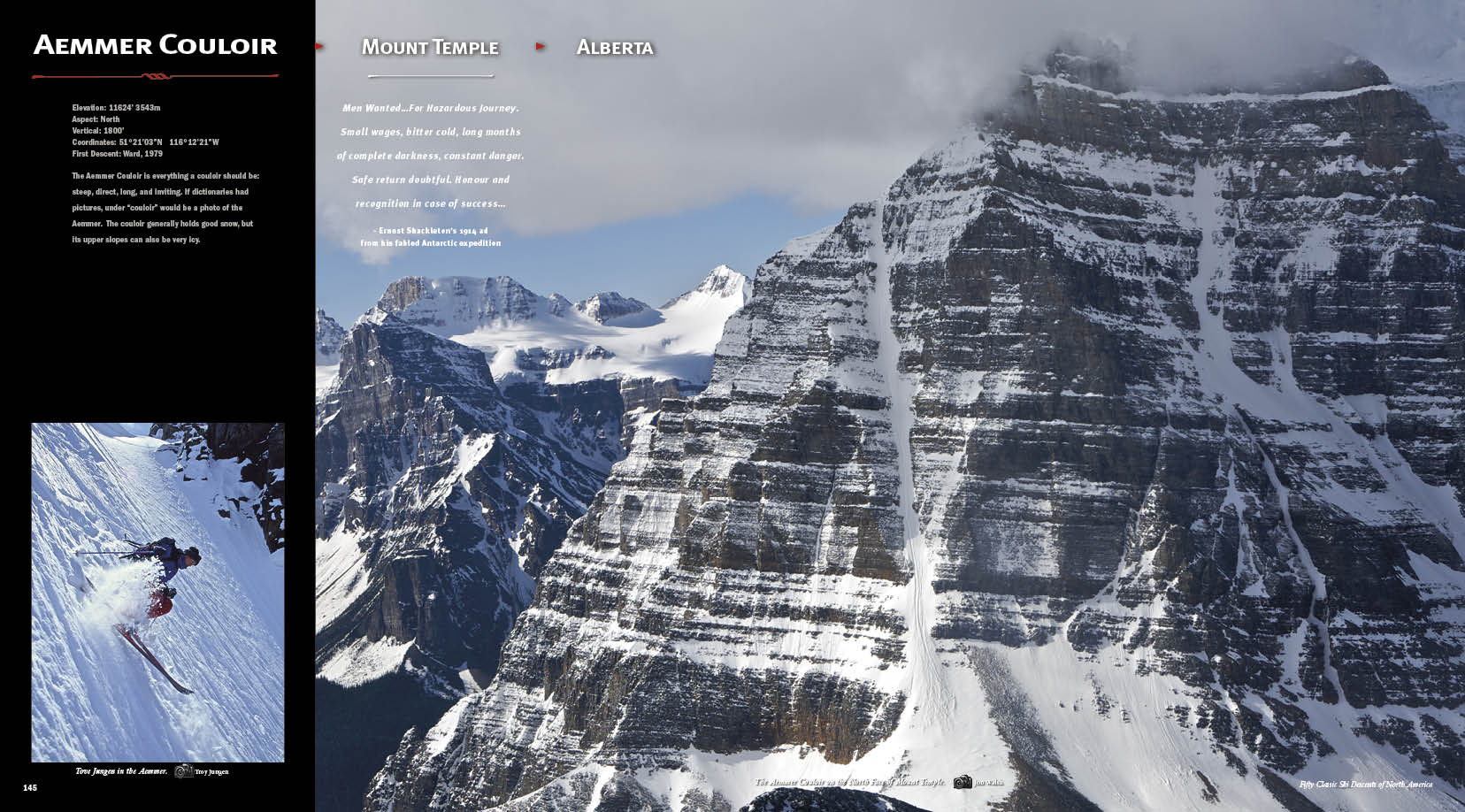

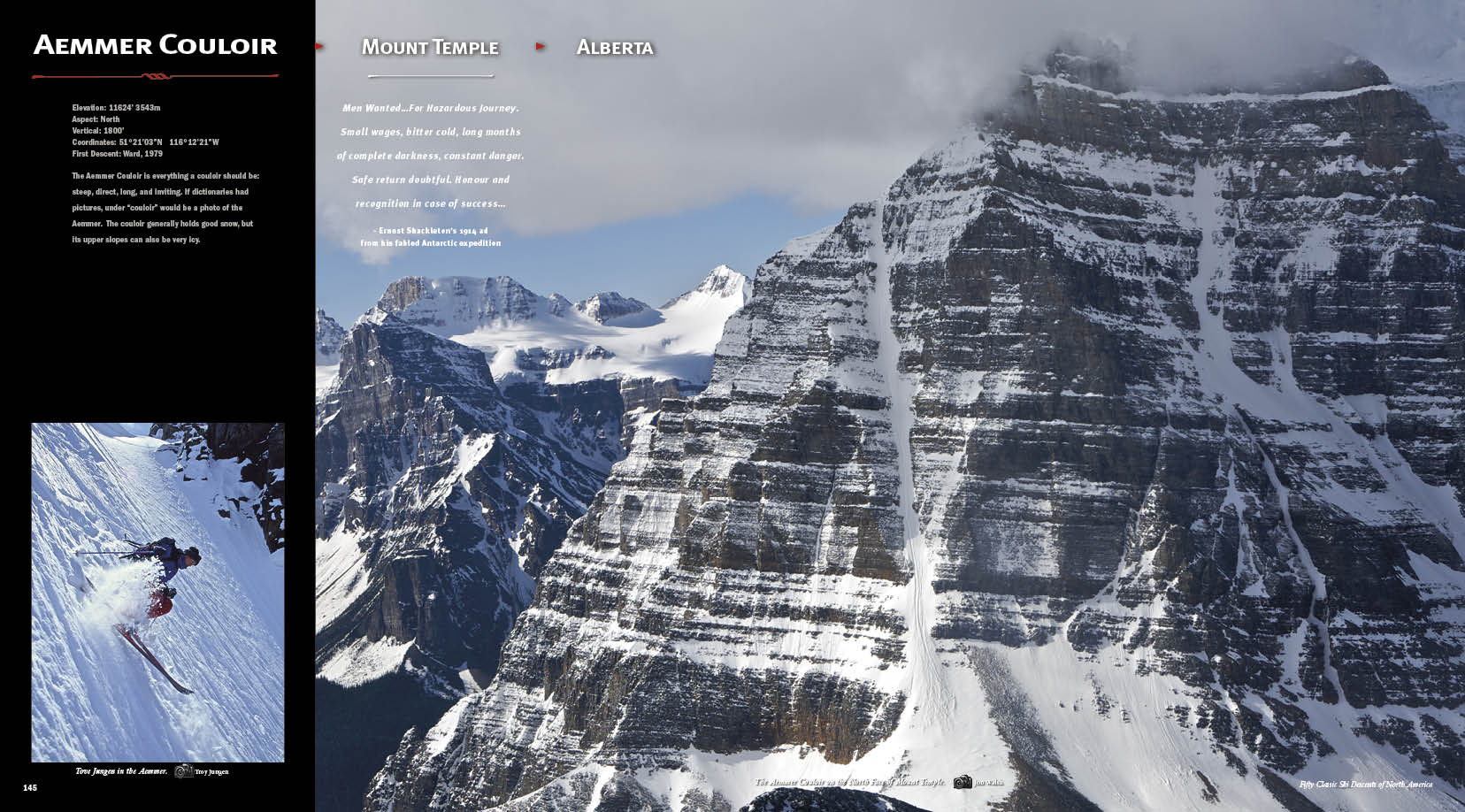

Visible from Lake Louise area and lifts this is just one of many big committing hits in the area. Jon Walsh had the best idea I've heard. Climb Mt. Temple via a classic ice route, traverse around to the Ammer and finish out with an amazing ski descent. Canadians love the Ammer zone, the area appears on the nation's currency.

On a recon mission a few years back I only stoked my FOMO for the Ammer. While researching the book to determine and ski some of the BC classics, Chris Davenport, Jamie Harris, Troy Jungen and I set out early one May morning to see what the Ammer was all about. I bailed about 2 hours in due to gaping, bleeding holes on each heal as a result of a traverse we did the week before. Troy was nursing a major hangover and ended up sleeping in the car most of the day (I guess when you're the first to ski Robson the Ammer is just childs play and not worth missing a good nap). Dav in his usual unstoppable style, jammed his way to the top of the couloir with Jamie in tow where they experienced excellent conditions for May. -Art

Men Wanted…For Hazardous Journey. Small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger. Safe return doubtful. Honour and

recognition in case of success…

- Ernest Shackleton’s 1914 ad

from his fabled Antarctic expedition

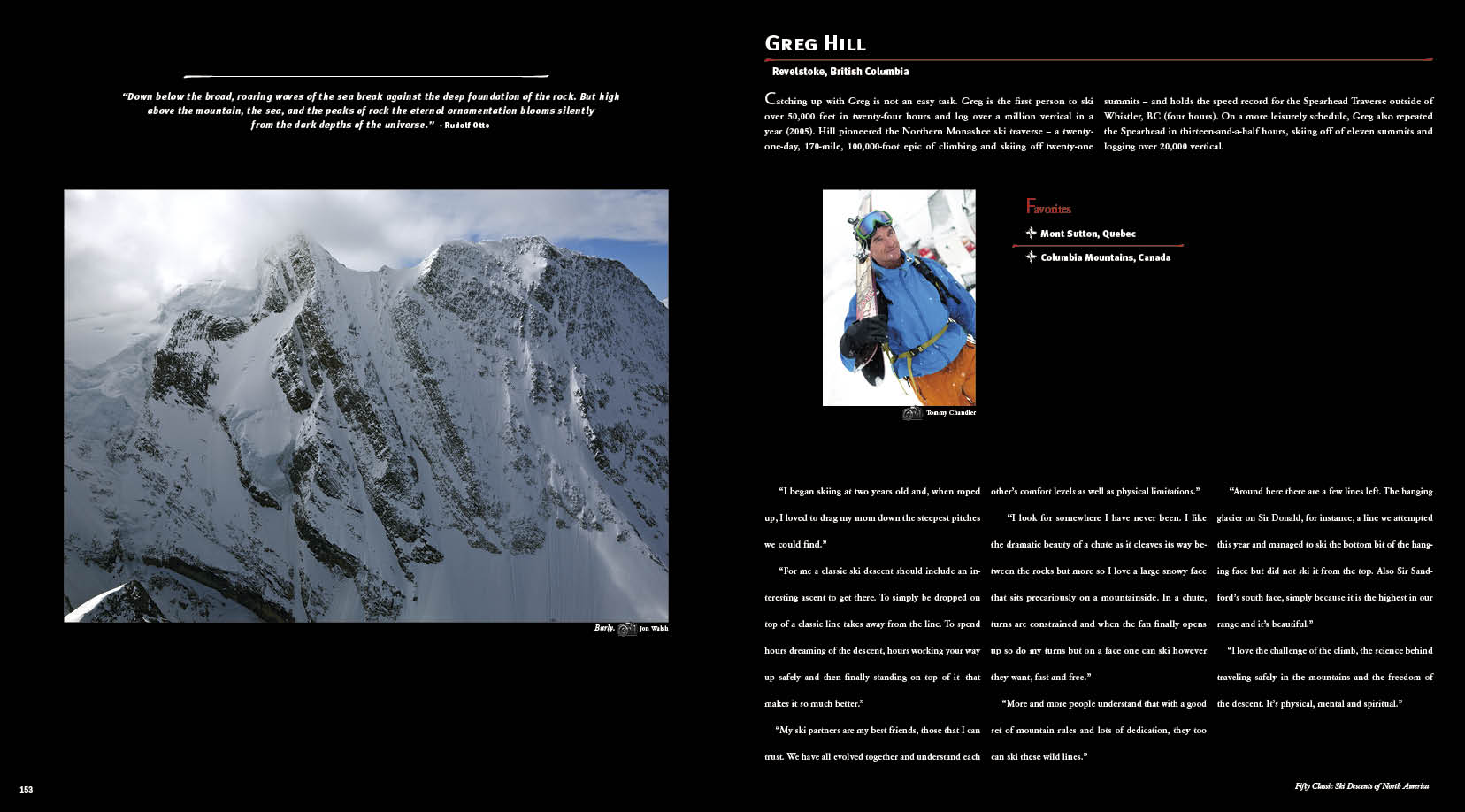

This descent is one that will take you a couple of days to approach, or perhaps if you would like to be one of Greg Hill's touring partners you will try to do it in a single monstrous day. But then again who really enjoys navigating through the mountains in the dark. - Art ... See Greg's comments on the next image to your right.

“Down below the broad, roaring waves of the sea break against the deep foundation of the rock. But high above the mountain, the sea, and the peaks of rock the eternal ornamentation blooms silently

from the dark depths of the universe.” - Rudolf Otto