Elevation: 6299’ 1920m, Aspect: North

Vertical: 1800’, First Descent: Rippey, Coombs

The Sphinx is one of the most jaw-dropping lines in the entire Chugach Range. It is sustained 50-degree-plus skiing with the added danger of the entire upper face funnelling into the gully above the exit. You better be good at sluff management on the Sphinx, or take it slow and easy.

One you've been to Alaska you realize just how many amazing ski mountaineering routes there are and how much more there is to explore. One can understand why some skiers will spend a lifetime searching the rare geography and glaciers of Alaska. - Art

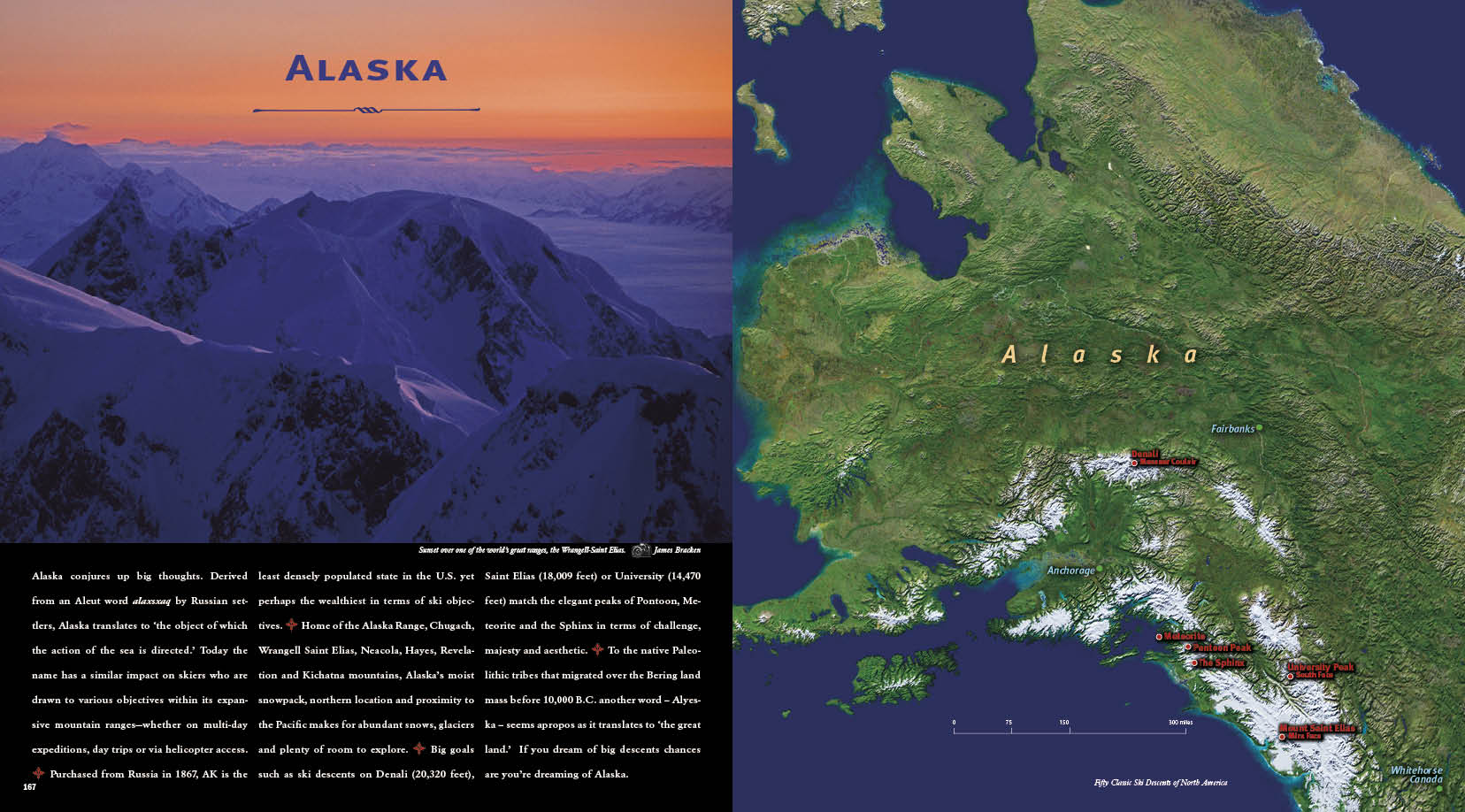

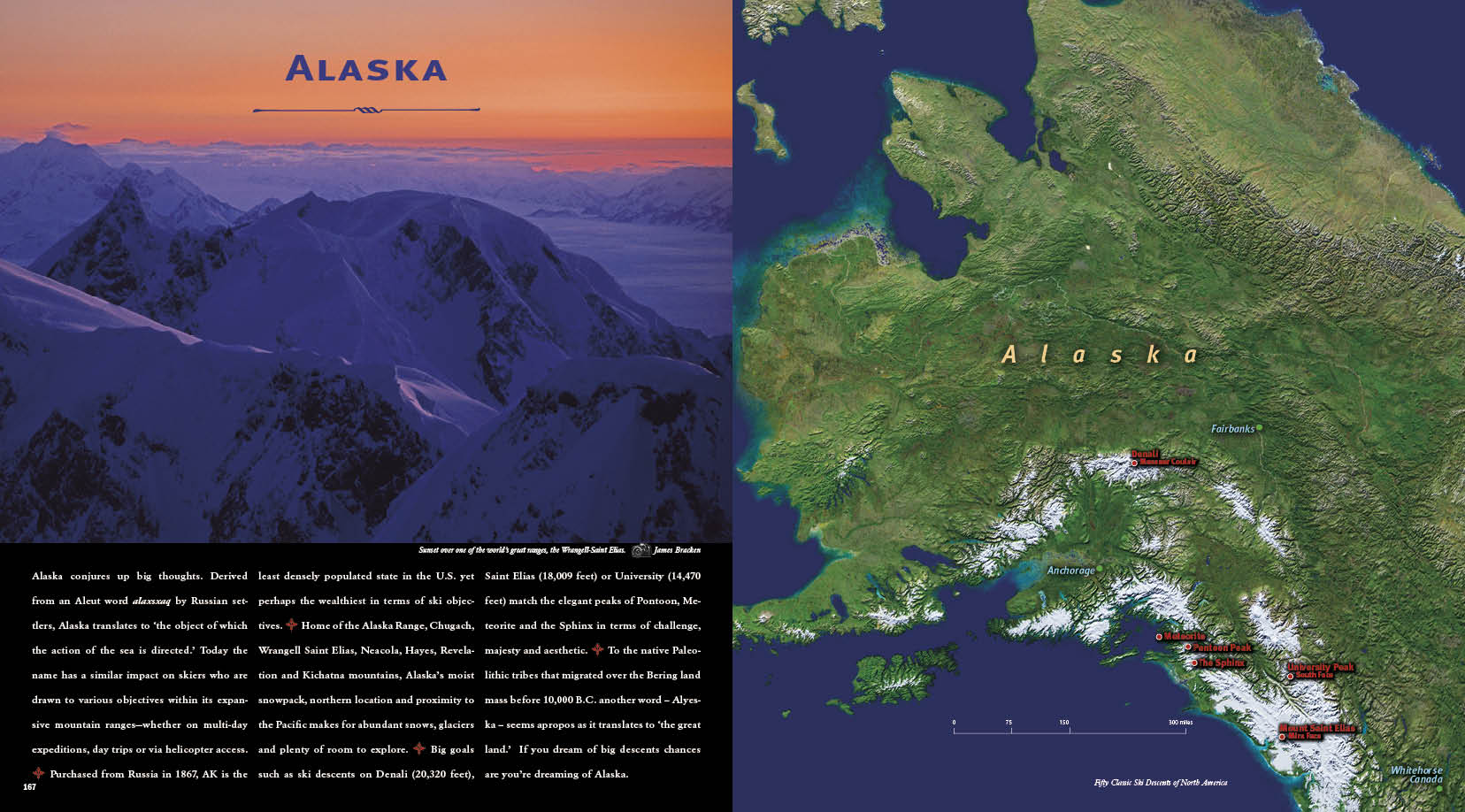

Alaska conjures up big thoughts. Derived from an Aleut word alaxsxaq by Russian settlers, Alaska translates to ‘the object of which the action of the sea is directed.’ Today the name has a similar impact on skiers who are drawn to various objectives within its expansive mountain ranges—whether on multi-day expeditions, day trips or via helicopter access. • Purchased from Russia in 1867, AK is the least densely populated state in the U.S. yet perhaps the wealthiest in terms of ski objectives. • Home of the Alaska Range, Chugach, Wrangell-Saint Elias, Neacola, Hayes, Revelation and Kichatna mountains, Alaska’s moist snowpack, northern location and proximity to the Pacific makes for abundant snows, glaciers and plenty of room to explore. • Big goals such as ski descents on Denali (20,320 feet), Saint Elias (18,009 feet) or University (14,470 feet) match the elegant peaks of Pontoon, Meteorite and the Sphinx in terms of challenge, majesty and aesthetic. • To the native Paleolithic tribes that migrated over the Bering land mass before 10,000 B.C. another word – Alyeska – seems apropos as it translates to ‘the great land.’ If you dream of big descents chances are you’re dreaming of Alaska.

"Earth and sky, woods and fields, lakes and rivers, the mountain and the sea, are excellent schoolmasters, and teach some of us more than we can ever learn from books." - John Lubbock

This Brad Washburn image shows the timeless power of the highest in North America. The Messner couloir presents itself as if to say harvest me if you dare, ski me if you respect this massive mountain.

Chris Davenport

When people ask me what my favorite ski descents have been, Denali’s Messner Couloir inevitably lands near the top of the list. In my twenty-odd years of ski mountaineering, rarely have I experienced the emotion that occurs as I traverse off the Football Field and onto the upper flanks of the Messner. I am in awe of my surroundings, if not a bit hypoxic from a dash to the summit from 14,000-foot camp up the Orient Express. I am nervous yet intoxicated by the simple beauty of nature in this high and wild place. I am anxious yet also feel a certain sense of calm. Every nerve in my body senses the snowpack as I slowly ski into the belly of the beast.

Had I just arrived on Denali, I would be in no condition mentally to handle a descent of this magnitude. The Messner is something you have to warm up for. And in many ways you have to let a route like this come to you, instead of the other way around. So my friends and I spend ten days warming up, waiting for the line to present herself to us. First, we must pay our respects. We ski the Rescue Gully, the Sunshine Couloir, the Orient Express, and some first descents off Black Rock Peak on the North Summit of Denali. Only then, when we find a deep appreciation for the scale of this massive mountain, are we able to give the Messner his due.

The day we ski the Messner is about as nice a day as one can have on Denali. We race up the Orient Express, feeling strong and confident.

Nick Devore and I continue to the summit and spend a few precious minutes enjoying the relatively warm, sunny afternoon. There is not even a breath of wind in the sky. The mountain gods are looking after us, and we can sense it. We ski down to the Football Field and southwest toward the top of the line, where we meet our friends and teammates Greg Collins, Clark Fyans, Kirsten Kremer, and Kellie Okonek. (Greg had just skied all the way up from the landing strip at 7,000 feet to meet us.) Together, the six of us move into •

the couloir and begin descending, slowly and with a bit of trepidation. Soon we realize that everything is perfect: the snow, the weather, the day, the moment. As our confidence grows so do our smiles, and we begin making big arcs across the upper expanse of the Messner. Even when you’re acclimated, linking lots of turns together at this altitude takes effort, so we take our time, gathering together to catch our breath, take photos, and admire our perch, some 4,000 feet above our tents below.

Before I know it I am negotiating the lower face, directly above camp. In this area the snowpack is thin and painted over solid black ice. From my experience skiing the Sunshine Couloir I know it is well bonded, so I take liberty to ski close to the ice, a sensation I have known only a few other times in my life. Back at the ‘Stronghold,’ our massive dome tent, a celebration ensues—a celebration of the mountain, the line, friends, and life. We are so lucky, so fortunate, and so blessed on this day. I often thank the mountains when I’ve had a wonderful ski descent, but in this case I feel an even greater bond with Denali, The High One, and with the Messner Couloir—a bond that I will carry with me for the rest of my life.

The first ascent team consisting of the San Juan Allstars grinds their way up one of the largest sustained faces in the St. Elias range and one of the biggest in North America, the South Face of University Peak.

Truly one of the largest and most intimidating and remote ski routes in North America, University's 7,000' south face is nothing less than ominous and beyond the scale of what any accomplished ski mountaineer would normally encounter during a full life of skiing.

Lorne Glick

Covered in perfect rippled powder. In April 2001 we stand at the top of it, humans truly blessed.

The year before, we’d seen the South Face of University Peak on our way to Saint Elias and made plans then and there. It’s impossible not to be drawn to a continuous 7,000-foot swath of forty- to fifty-degree snow plastered on a dramatic Alaskan peak.

Then Kristen writes it up in Powder magazine and everybody and their brother is gunning for it. We decide to go early, keep our plans to ourselves. The team changes. James and Doug can’t go. A couple of San Juan superstars, Lance McDonald and Bob Kingsley, sign up. Then Andy’s knee makes that popping sound. A last-minute call to New York and John “Weedy” Whedon is in.

There’s really no way to grasp the scale of this feature from below. After the flight in, we go a few thousand feet up and dig out a platform under a little outcrop. Back at camp, with a little more perspective, we realize that’s not such a good place to hang. Different angles, a little fresh snow, changing light, a bigger storm—we just observe for the next week. A powder cloud envelops base camp one day. We make offerings of our finest.

“We’ll just have to go for it in one push.” Our Alaska factor is to multiply climbing time in the Rockies by two. For some reason this seems to work out precisely.

“Since we’re up, we might as well ski up the glacier for a while.” Off at 9 p.m. in light snow. A few stars peek through, then a full moon. Glory! Ever upward through the night. Dawn. A few snapshots. We’re still climbing. The sun is on us for an hour when I notice Weedy’s headlamp still on. He slumps over his axes as I switch it off and squirt GU into his open mouth like a baby robin from the lowlands.

Just off the top of the face, we’re pulling the rope after •

the 200-foot V-thread rappel down the seventy-degree ice flute. Bob decides to start San Juan–style by jamming his tails straight back into the snow and then stepping into his bindings. After standing there for a few moments, looking down between his tips, he carefully takes them off.

Near the top, I’m making a jump-turn in front of Weedy when I catch my tails. Instantly I’m headfirst. Like a cat thrown across the room onto the drapes, both steel claws sink to the hilt.

“Please don’t do that again,” Weedy mutters.

Many turns later, Paul’s Beaver drops over the ridge carrying the first of the grant recipients in their newly minted outfits. They got stained that night by beer exploding off the ceiling of the Megamid. We even have a surprise knock on the door just before dark. Paul had silently glided the Super Cub in with even more congratulatory beverages.

I’ll be the first one buying when someone skis the south face of Uni from the summit.